Interviewed: Sokol Paja/

*Dr. Kimberly Kalaja is a filmmaker, screenwriter, playwright, author, & Fulbright. She earned her Ph.D. in Comparative Literature from Princeton University, an MA in Irish Literature from The Queen’s University of Belfast, and a BA in English at Scripps College. After working for 25 years as a Professor, she now dedicates her time to writing. Kimberly believes that stories are the foundations of identities, that they have the uncanny power to shape our realities. Her ambition is to craft meaningful, entertaining stories that encourage self-awareness and initiate conversations about the way we define ourselves as local and global citizens. She is committed to the free exchange of ideas among individuals and cultures, to the celebration of intellectual and cultural diversity, to open debate, and to freedom of thought and speech.

Dr. Kimberly Kalaja, what was it like living in Tirana during your Fulbright?

Living in Tirana was an incredible experience. I had the honor of lecturing as a Fulbright professor on American literature and culture in the Fakulteti i Gjuhëve të Huaja at the University of Tirana back in 2010-11. Of course it was a different city 15 years ago. There has been considerable population growth and economic development since then. What I remember most is how welcoming the city and its people were, both at the university and in my personal life. Much of my husband’s extended family lives in Tirana. So, I was extremely lucky that, along with the formal experience of having an academic job, I also had the informal education of being integrated into an Albanian family as “nusja.” My memories of being in the classroom at the university are inextricably mixed with those of debating politics with my husband’s uncles and learning to cook traditional Albanian recipes with my adopted teze. I feel enormous warmth and gratitude whenever I think of Tirana.

How did you first become interested in Albanian literature and politics?

When I was in my doctoral program at Princeton University, my thesis advisor was David Bellos, who was Ismail Kadare’s English-language translator. I was the preceptor in his Modern European Literature course, and he put Kadare’s Broken April on the syllabus. Teaching Kadare to Princeton undergraduates, I realized how integral Kadare was to the European literary canon. As 20th century European literature was the focus of much of my teaching, I was eager to read more of Kadare’s work and learn more about Albanian literature in general. It must be said that Princeton’s comparative literature department is very strict: Ph.D. candidates are required to speak and read the language of any author they research and are not allowed to work exclusively with translations. So, I began the journey to learn the language. I was lucky enough to land a fellowship at the Comparative Language Institute in Arizona where I began my studies with Linda Mëniku – a professor of Albanian language and true cultural ambassador. Linda was the person who first encouraged me to apply for a Fulbright, and it sort of snowballed from there. Albanian has proved to be one of the most challenging languages I’ve studied so far. Luckily, as David Bellos was Kadare’s translator, I was allowed to work with English translations for teaching. I continue to be a student of the language.

What aspects of Albanian politics, culture and economics do you find most interesting?

It’s difficult to say, as an incredible amount of intellectual progress has been made in the last fifteen years. For example, back when I was first in Tirana, very few people would have been interested in my first book, Reading Games (Dalkey Archive Press 2007), which posited a literary theory of human creativity based on the intersection of mathematical game theories and post-modern experimental literature. Back then, discussions of artificial intelligence did not have the broad cultural appeal that they do today, though I have been interested in AI in my teaching and research for decades. Reading Games is not about AI per se; my focus is not on technology or marketing. I am interested in the nature and origin of human creativity and inspiration in the generative arts, and therefore that book has important ethical implications for the AI debate. I love that engineers like Mira Murati are becoming public figures and thought leaders. Mira has brought global awareness to Albania’s cultural contributions and potential — recognition long overdue. As a result of the proliferation and accessibility of products like OpenAI, there is more discussion of the ethical and philosophical issues at the heart of non-human creative potential. I would love it if there were more rigorous examinations and informed discussions concerning the intersection of technology and the humanities. The future holds a lot of promise, and Albanians will have a prominent seat at that table.

Are there any Albanian themes or subjects in your literary and artistic work?

I hope that the themes and ideas in my work are universal, but private and idiosyncratic experiences inevitably shape the subjectivity, perspective and voice of any writer. It is sometimes difficult to sift out which elements of my consciousness were shaped in what places. For example, I grew up in Orange County, California, earned my first master’s degree in Belfast Northern Ireland during the war, wrote my first book while living in Paris and Princeton, and finished writing my first feature-length play while living in a transitional Tirana. That said, the play I finished while living and working in Tirana — Night Moths on the Wing – is more deeply influenced by Balkan culture and politics than anything else I’ve written so far. Immersed in Balkan culture for the first time, I became very interested in how charismatic personalities – all throughout the Balkans — could rise to political power and what made people so devotedly loyal to leaders who were not always working in their best interests.

What were the differences between teaching at American Universities and at the University of Tirana?

American students who are privileged enough to enter higher education take their education for granted – there is no disguising this. Perhaps it is an inescapable aspect of privilege that when things are easy to come by, they are not always appreciated. But this was not the case with the students I worked with in Tirana. In this way, my experience at UT was inspiring. The students were curious and eager to learn; overall, they were self-aware and even self-conscious of their limited exposure to certain ideas; they felt “behind” and were painfully aware of how limited their opportunities would be without an education. I would describe them as hungry – for knowledge, for skills, for travel, for experience, for opportunities. Working with this kind of motivated student makes teaching meaningful. It was immensely rewarding.

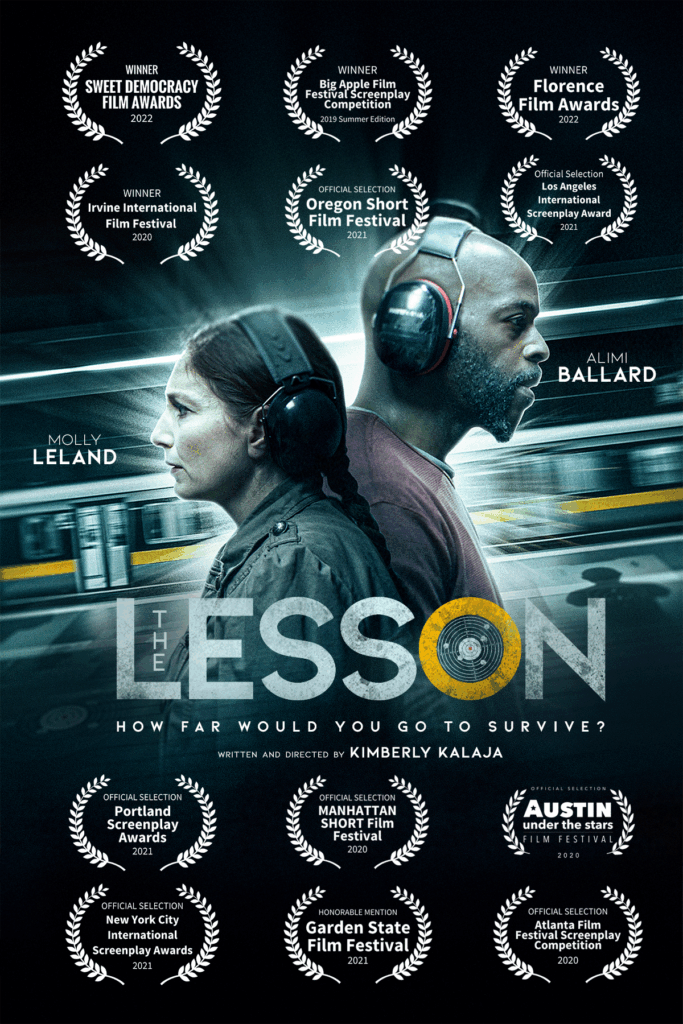

Could you tell us a little about your film The Lesson? What inspired you to make this film?

The Lesson (2024) has just been released and is on the festival circuit. It is an adaptation of a play I wrote back in 2016 called The Shooter. It re-frames the dialogue about guns in America – shifting the discussion away from guns themselves and onto the human experience of gun ownership and gun violence. It is an unusual film about guns in that it is not really about guns at all – it is not a “statement” film; it is instead an exploration of survival and recovery. In the U.S. we have become highly polarized on a lot of political issues – and guns is one of the most sensitive issues around. Unfortunately, even in the arts, a place where voices that challenge the norm should be extolled, for the past couple of decades or so, audiences have become accustomed to seeking out stories that reinforce what they already believe and, consequently, have become increasingly suspicious of anything that doesn’t immediately announce a political stance. We are becoming trained to resist anything that challenges us. It is a scary time for artists; if we try to have a discussion that is genuinely non-partisan, we risk having people on all sides disengage or feel threatened. The Lesson is a consciously and vigilantly non-partisan film. I set out to make something in the tradition of the art that I admire – art in which conflicting values and ideas are sincerely and sensitively explored without judgment. My hope is that this small film will find its audience and spark meaningful discussions. It was screened at the Sedona International Film Festival earlier this year and was very well-received. That was amazing. It has since been invited to a couple of private screenings by art enthusiasts that will take place later this year. Slowly and steadily, I’m hoping to get the word out. Ngadalë Ngadalë as my husband would say.

What is your next project? Are you working on something now?

Currently I am in pre-production (that’s the fund-raising and team-building stage) for my next short film Acts Without Words. This screenplay too was written originally as a play, and I am adapting it for the screen. It is more formally experimental than The Shooter, in that it is dialogue-free and communicates the story exclusively through movement. It will be choreographed, like a ballet, but with natural movement. It will rely heavily of stunning visuals. So, scouting locations and finding a talented crew who can help me realize this new aesthetic are my first priorities. I am seriously considering shooting the film in Albania if I can find the perfect setting. I’ll start scouting locations later this year.

Photos / Attachments:

The Lesson movie poster

Kimberly with Ismail Kadare in Tirana 2011

Left to right: Dorjan Kalaja, Kimberly Kalaja and former U.S. Ambassador to Albania, Alexander Arvizu

Kimberly, Vlorë, 2011

Contact information:

www.kimberlykalaja.com

www.thelesson-thefilm.com

IG: @kimberlykalaja24

“The Lesson” Trailer