Nga Julika Prifti/

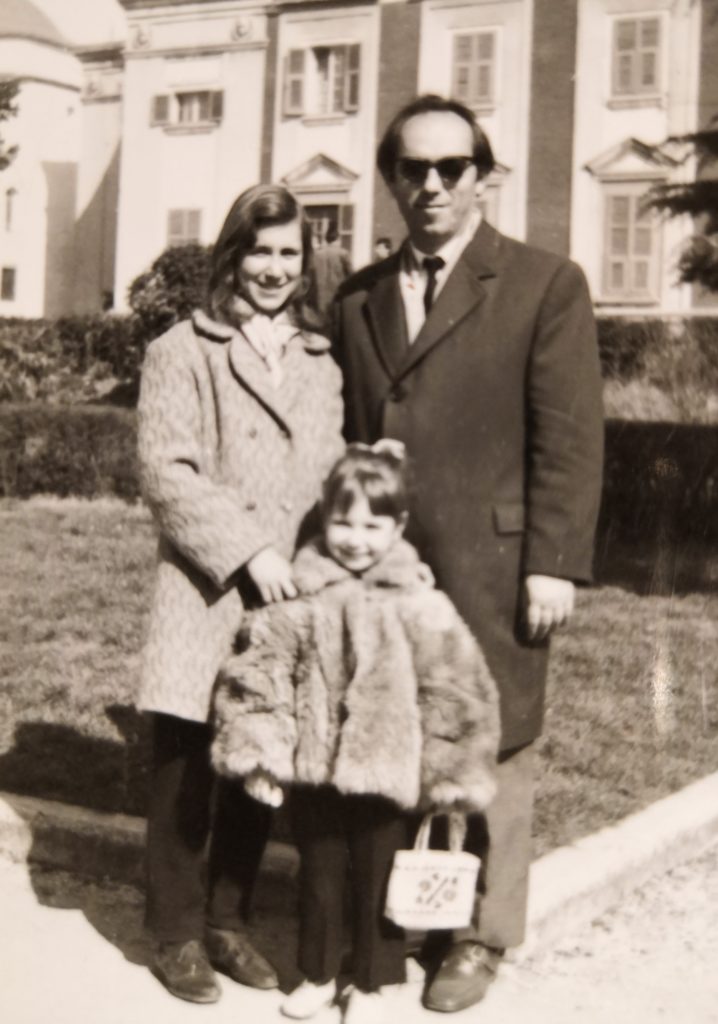

This year my Father’s Day wish is distinctively exceptional. In January, I celebrated my 60th anniversary and having both parents at the celebration was truly the most precious gift. My mom and dad married young and had three girls shortly after their wedding year until the late sixties.

My father did not call any of us “Princess” or by any other aristocratic tittle. We were born and raised in socialist Albania where nobility rankings were execrated and vilified. Even if such nicknames would be commonplace, my dad would not have chosen royal terms that would place one “above” the others as if being born in a higher cast. My father did not believe, nor did he own any tittles. Through his works and publications, he earned plenty of professional credentials such as novelist, screenplay writer, essayist, publicist, playwright, comedy and vaudeville writer, children’s author, teacher, professor, storyteller, translator. The versatility of his talents is unsurpassed by any living author in Albania.

My father didn’t choose tittles to make us special. We were his daughters and that made us “one of a kind” in a package of three. Albania’s patriarchal society cherished the birth of a son as a secure way to preserve the name of the family. Traditionally, a son would inherit the parents’ property and was responsible for the parents’ wellbeing. As girls, we thought the family missed having a boy. My mother did express her grievances about it for a long time. She felt that my father’s family regretted the fact that as the daughter-in-law, she did not give birth to a male child. And perhaps there was truth to the rumor that our great-grandmother had said “Girl again!’ when the third one was born to our family. Yet, I never heard my father voice any disappointment ever. In the beginning, it did make me sad that my mother missed having a son. Perhaps, as a middle child, I was the one that was meant to be the boy of the household. About ten years later, I got a bit upset when chances for a male heir were lowered even more as the third girl arrived. Three girls! Zero boys! As time passed, I remember that the mental burden was lifted. I thought to myself that we would be able to keep our maiden names so our father’s last name would live on. We would divide everything in three equal parts. I felt empowered by the fact that I never heard my father complain about having three daughters or have any resentment about us. I really wondered how my father who was raised in a remote village, south of Albania was so free of the patriarchal mentality. To him, a child was a great gift to be loved and cared for, to be cherished and taught about the ways of the world. Aside from being a talented writer, my father was ahead of his time as a thinker and a teacher. Like many males of the village, his father, Rafael, had immigrated to America. It was my grandmother and great-grandmother who raised him while doingmanual work, minding the cattle and taking care of all house chores. His level was emancipation was unique for Albanian men and society in the past and even now. In many respects, my father was a self-made man. When it came to schooling, he was self-taught in several language courses. His job as a reporter for magazines or newspapers took him outside the city and around the country. Yet, he tried to pursue learning in any way he could. I remember his taping on the magneto phone in French, English, Italian and Russian. Years later, as a freelance writer, he brought into Albanian literature translations of classic books like Little Prince, Charlie and the Chocolate Factory etc., that are beloved treasures for posterity.

Curiously, my father never told us to learn this or that language. We learned by example. He was not going to push us to do this or that. He trusted us to choose our vocation as best suited us. By the time I was ten years, my dad was a notable published author in Albania. Yet, he was as down to earth as ever, unlike some writers who saw themselves as ‘important’ at that time. I went to school with the privileged and entitled children of some these influential authors. They have made careers out of their father’s status and have no credits to their names.

In winter, my father would go downstairs to chop wood for the stove. In the time of communist Albania, each family got a rationed firewood delivery. As soon as the utilities truck moved out, we, the kids,carried handfuls upstairs to be used that night and tossedsome in a basement of the apartment building. Our wood-burning stove was the source of heat but since it was an old model, it only fitted well chopped firewood. To start the fire, we also needed some really thinly chopped firewood. Dad made the whole experience enjoyable. He would start cutting and then let us take turns holding the handle and sliding our hands close to the axe’s head. There was a method to it!Another favorite activity of my father was cooking. At the time, very few Albanian men would find themselves in or find their way around the kitchen. My dad prepared the best dishes. Unlike mom’s cooking, his was not a chore. He did it with love and pleasure, Also he applied science to it, like the right temperature and proper measurements. I remember he bought cooking books and looked up recipes. He enjoyed eating and drinking socially. Two of his close school friends, DhimiterXhuvani and Tahir Cenko even produced homemade grape raki. It was a kind of experiment that my father would not pass out on. I remember that when the grapes were fermented and ready to be brewed, his friends came over and tried the first batch. While drinking and laughing, they all enjoyed one another’s company.I believe that it taught me how to pick trusted friends and devoted buddies and how to share a good time with them. Since my father could approach every task from woodcutting to cooking without prejudice, I was educated to appreciate every duty and person with no bias.

Most of all, my father gave us a good life in socialist Albania. After writing the stories and fables, he would read them out loud making us his first audience. He created some of the stories specifically for us. In one of them, the Water Drop(Pika e Ujit) I discovered how circulation worked without even realizing it was Science. In another, Squirrel’s Visit to the Dentist (KetriShkonteDentisti) I realized the importance of dental hygiene as a child. Thanks to his translations, we were introduced to famous world writers like Hans-Christian Anderson. Under a repressive socialist system, my dad created a world of honorable characters, good morals and ethical lessons for life. We went to see his plays, the comedies and movies about patriots like the one about Petro NiniLuarasi. We were touched and moved by his creations. Once you read a novel written by my father, you will remember it forever. In each one, there are genuine and tangible characters that relate to you in a lyrical language that is honest and true, rather than glittery and fake. After one read, his stories live in your memory.

On this Father’s Day, I thank my dad for making the world a better place and our happiness a matter of paramount importance. I thank him for sharing the life’s pain with me and taking some of my suffering away. I thank him for seeing me every time and even noticing how I was deeply troubled by the Rozafa legend. The burying of the youngest, the best and the most loved daughter-in-law caused me immense pain. Why was she the one to be sacrificed? Why did the older brothers tell their wives not to bring lunch to them at the fortress? Why did two of the brothers who made the same pledge break their promise (Besa) and the third one who loved his bride dearly did not? My dad, who is an avid admirer and researcher of Albanian folklore, identified an old version of the legend. Based on it, he created a masterpiece novelette about Rozafa’s castle. It is not a story of a broken promise or betrayal but a story of self-sacrifice. The young bride was told about the plot too. Rozafa sacrificed herself willingly for the good of her people. If she did not go to the castle then who would? She accepted the sacrifice as an honor.

Today, on Father’s Day, in the pandemic era, I cannot give him a kiss or a hug; I have to wear a mask and stay six feet away, yet this card tells him that my life is much better because of my dad.

I hope I am my father’s daughter!

For me, there is no higher title! Thank you, Dad! I love you!