PREFACE

By prof. Nicholas C. Pano

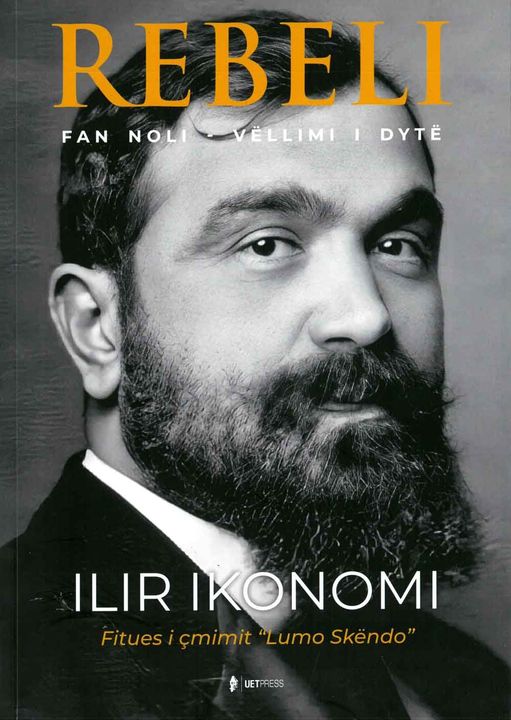

In this second volume of his authoritative biography of Fan Noli, Ilir Ikonomi focuses on the life and activities of Noli during the years 1920-24.The primary locus of Noli’s activities during this period shifts from the Albanian community in the United States to Albania and Europe. These five years will mark the zenith in what may be termed the public phase of Noli’s life and career,

As documented by the author, in the first volume of this work, Noli had by 1920 emerged as the dominant personality of the Albanian-American community and his travels to Albania and the Albanian colonies in Europe between 1912 and 1915 had further burnished his credentials as a patriot and activist. His reputation within what might be termed the Albanian world of this time was attributable to the leading roles he had played in the establishment of the Albanian Orthodox Church in America (1908), the newspaper Dielli (1909) and the Pan- Albanian Federation of America Vatra (1912). All of these entities, as significant and effective agencies of Albanian nationalism, had propelled the Albanian-American community to the forefront of this movement. Noli’s rise to prominence was enhanced by his broad array of contributions as a clergyman, author, lobbyist, orator and organizer to the Albanian national cause. Noli’s Harvard degree had also served him well in his advocacy in behalf of Albania both in the United States and abroad.

The Albanian phase of Noli’s career stemmed from the decision of the Albanian Orthodox Church in America with the endorsement and financial support of Vatra to promote the establishment of an autocephalous Albanian Orthodox Church in the homeland to counter Greek claims that all Albanian Orthodox Christians were Greek and the territories they inhabited were rightly part of Greece. To advance the fledgling efforts to form a national Albanian Church, Noli along with Fathers Vangjel Camce and Vasil Marko travelled to Albania in July 1920. The two priests were permitted to enter the country. Noli, however, was denied admittance apparently on such grounds as concerns regarding his non-canonical episcopal ordination in July 1919 and fears that he might be a disruptive political influence within the country.

Noli had remained in Europe and in November 1920 he was asked to head the Albanian delegation to the League of Nations to make the case for Albania’s admission to that organization. As the author demonstrates, Noli’s diplomatic skills were essential in the building of support for the unanimous vote to admit Albania to the League on 17 December 1920. Noli often observed that he regarded his efforts leading to the admission of Albania to the League as the most important achievement of his public service. Noli’s successful mission in Geneva served to enhance his popularity in Albania and he would subsequently be called upon to represent Albania on other issues affecting the country at the League of Nations.

In April 1921, Noli was appointed by Vatra to fill the seat in the Albanian National Council, as the Albanian Parliament was then known, that had been awarded to that organization in recognition of the valuable service it had rendered to Albania and its people. This was the beginning of Noli’s intensive involvement in Albanian politics. He would become a major player in this arena between 1921-24.

The years 1920-24 are among the most complex and confusing eras in Albanian history. During this four year period, there were twelve government changes with nine different prime ministers. The Noli cabinet (June-December 1924) was the last of these. Fortunately, Ilir Ikonomi provides reliable and skillful guidance in understanding the politics and personalities of this turbulent time.

Noli’s short-lived government was doomed to fail for a host of reasons that the author addresses. These range from the lack of unity within the leadership of the ruling coalition and its supporters, the inability to obtain much needed external funding, unwillingness of foreign governments to recognize the revolutionary government that did not seek to legitimize its status in a timely manner, establishment of diplomatic relations with the Soviet Union to Noli’s lengthy absences from Albania and the premature announcement of his 20 point reform program that unrealistically raised the expectations of his followers and further alienated the opposition.

Although Noli was mainly focused on politics and diplomacy between 1921-23, he continued to encourage the initiative to establish an autocephalous church. And, on a more personal level, the troublesome issue of Noli’s irregular episcopal ordination would be resolved by his canonical ordination on 4 December 1923. He, however, disappointed some of his political rivals who hoped that the Bishop would now abandon politics for religion. And, as he was transitioning to the political phase of his career, Noli had managed to complete and publish in 1921 his Albanian-language popular biography of Skanderbeg which was intended to raise the national pride and consciousness of his compatriots. Although this was not a productive period in respect to Noli’s literary output, it was in respect to his oratory. For this reason, the author has included in this book the texts of three of Noli’s oratorical masterpieces delivered during 1923 and 1924. The most famous of these is Noli’s League of Nations 10 September 1924 address requesting economic assistance for Albania from the that organization. The speech is a rhetorical gem which was well received by many in the Assembly Hall and by much of the European and U. S. press of the time. Unfortunately, the League was no in the position to provide or guarantee a loan to Albania. The sarcastic and patronizing tone of the speech and its mockery of the League and the parliamentary system offended some European political leaders and members of the Albanian-American community, including Faik Konica.

With the demise of the Noli regime, Albania’s brief flirtation with representative democracy will come to an end. The country will will assume the form of an authoritarian republic.

With the departure of Noli the outsize influence of the Albanian-American community in the homeland will begin to decline.

With the collapse of Noli’s government about a dozen of his radical followers will make their way to the Soviet Union where they form the Albanian Communist Group and after training and indoctrination will be dispatched to Albania or Albanian communities in Europe to organize communist cells or groups.

In the aftermath of his flight from Albania in December 1924, Noli will go into exile, mainly in Austria and Germany where he will become affiliated with several Comintern funded organizations between 1925-29 when he breaks ties with these groups and announces his retirement from politics and desire to return to the United States. But these chapters in Noli’s life will be among the the topics covered in the next volume of this well written, well documented, nuanced account of Noli’s life that is a masterful combination of biography and history.

* Professor Emeritus of History, Western Illinois University