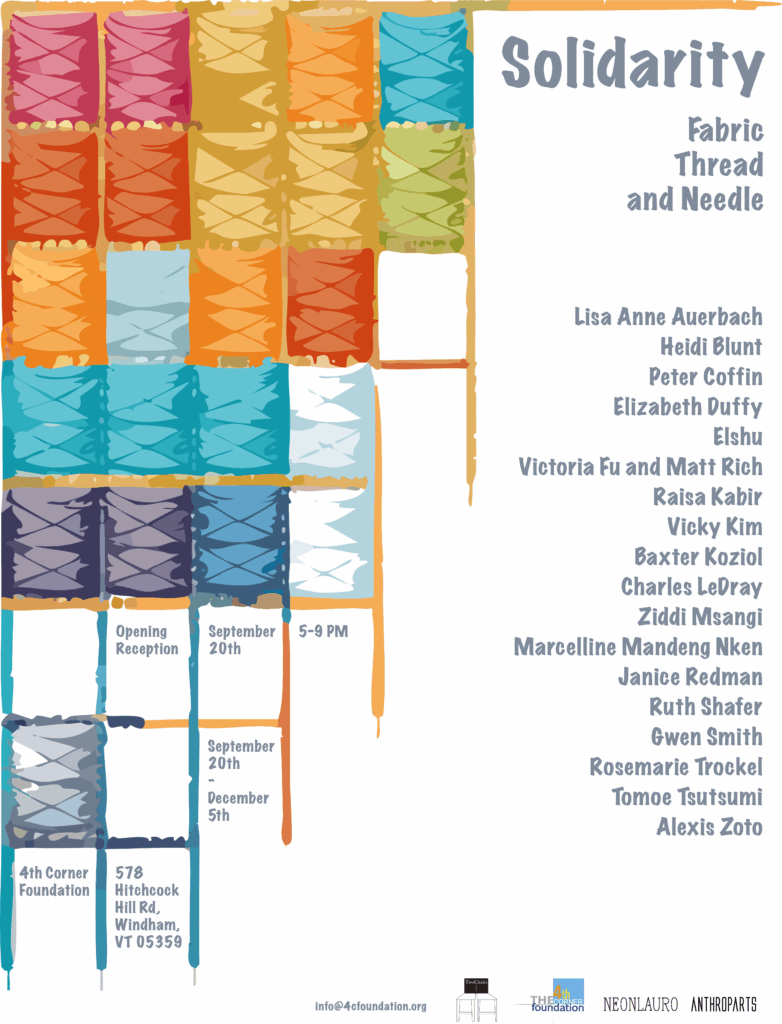

Opening Reception, September 20th, 5-9 PMSeptember 20th–December 5th 4th Corner Foundation578 Hitchcock Hill Rd, Windham, VT 05359info@4cfoundation.orgOn view through December 5thMonday–Thursday 10:00-4:00, Saturday and Sunday by Appt. Only4th

Corner Foundation and 2chairs are pleased to present Solidarity: Fabric,Thread and Needle, an exhibition that gathers together a selection of textile-based works by contemporary artists. The word ‘Solidarity’ is important because it conveys a sense of cohesion and interconnectedness that many of these works materially inhabit. The needle is critical given its essential function, working in harmony with thread to join one thing to another, as artist Louise Bourgeois describes: The needle is used to repair the damage. It’s a claim to forgiveness. It’s never aggressive, it’s not a pin.[i]The hand putting it to use, whether mending a sock or turning fabric into garments on an industrial sewing machine, has traditionally been gendered female. In one of the deadliest accidents in the history of the garment industry, the 2013 collapse of the Rana Plaza complex in Bangladesh, most of the workers were women. The impetus to produce fabric faster and more efficiently was closely tied to the advent of the steam engine. The shift from water power to steam and its reliance on fossil fuel gained traction in Britain and the US as it freed textile manufacturers from the requirement of siting factories near sources of moving water, resulting in the period we now refer to as the Anthropocene.

The artists in this exhibition, through the use and transformation of textile based materials explore conceptual, political and narrative concerns in a variety of ways that provide partial answers to a series of questions related to the social role of art posed by artist Thomas Hirschhorn in 2024: How to do art in times of war, destruction, violence, anger, hate, resentment? What kind of art should be done in moments of darkness and desperation? Can art be a tool for understanding history’s changes? Can a work of art draw alternative forms of understanding the world? How to continue working–as an artist–and in doing so, avoid falling into the traps of facts, journalism, and comments?[ii]The gallery space at 4th Corner Foundation offers a unique example in support of the notion that architecture may have its origins in weaving. Its interlocking interior walls, like woven threads–warp and weft–create a visually porous yet structurally sound environment, an ideal setting for an exhibition that reflects the bonds between material, maker and community.

Alexis Zoto’s most recent work consists of handwoven tapestries made from everyday materials such as her child’s shoelaces, discarded clothing and dry cleaning bags that combine with embedded texts to present the viewer with conflicting messages, personal thoughts and advice that may have filtered through generations of her matrilineal heritage. The viewer reading these works may feel they are caught in the middle of a conversation. Zoto explains that her work “is informed and inspired by her Albanian Orthodox heritage and her experiences as a woman, artist, educator, wife, and mother.” Zoto credits the Albanian weavers she interviewed for her scholarly work on kilims as the reason she began weaving as a way to better understand their process.

British artist Raisa Kabir notes that a local plant variety of cotton from Bangladesh went extinct largely due to the adoption of the American long grain cotton plant, harvested by enslaved persons, and uniquely suited to machine production. The juxtaposition between hand and industrial weaving is dramatically demonstrated in two works by Kabir, one woven by hand and the other by machine. Kabir describes her work as rooted in research, revealing how British and European industrial textile manufacturing extracted intellectual property (designs and techniques) and labor from India, resulting in the destruction of local organic cotton production as well as its thriving hand weaving industry. Kabir describes her practice as “weaving resistance” concerned with the “interwoven cultural politics of cloth” striving to re-imagine the world through weaving, performance and writing.

Ziddi Msangi’s graphic work explores the form and content of East African Kanga cloths as a transcultural form of visual and textual communication. Msangi, like Kabir, is also concerned with the global networks of textile manufacturing built on the backs of enslaved persons and unethical labor practices that continue to this day. Msangi writes: “The Kanga’s high-quality cloth was printed with resist, block, or hand-painted African visual language on bolts of fabric steam milled in Massachusetts made from white cotton picked in the Carolinas. The enslaved Africans in the insidious Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade labored to produce the cotton as a commodity sold back to Africans in a system designed to enslave black bodies.” Msangi’s designs incorporate critiques of power, male privilege and identity as shaped by historical and cultural narratives.

In their collaborative work Victoria Fu and Matt Rich embody Louise Bourgeois’ idea of the needle as a tool of care and unity. Fu, a moving image artist, and Rich, an abstract painter, join together their separate practices both conceptually and materially. The results are playful works that operate within a space of critical tension, and can be read simultaneously as paintings, sculptures, photographs, and functional objects. Loosely based on the “humble” apron, an item of domestic labor intended to be of use, the works are designed for a body (or bodies), are all flat and frontal, and have straps. The textile-based objects are sometimes installed on the wall as paintings, draped over furniture and walls, or hung on hooks for the public to try on. Fu and Rich have frequently collaborated, giving over their works to be activated by others. For this exhibition, collaborator Marcelline Mandeng Nken will perform with one of their works at the opening.

Gwen Smith uses fabric, either silk indigo dyed by the artist or African block print, to fill in the voids cut from photographic contact sheets celebrating her bold embrace of surfing. Poetically merging her personal history as a surfer with Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick; or, The Whale, Smith claims the sea for herself as a black woman, mother and artist echoing artist Hannah Brönte’s assertion that “an element as monumental as the ocean is colonized by this heteropatriarchy; it should be for everyone but it’s not.”[i] The title Mocha Island references the Chilean island where stories abound of a notorious white whale responsible for numerous shipwrecks and notably the inspiration for Melville’s novel. In Stripped Bare (Costa Rica) the bright fabric illuminates the blank forms to amplify the joyful core found in the often stigmatized experiences around womanhood and blackness. The fabric used in Smith’s work follows the search for indigenous pathways to map Black Leisure.

Vicky Kim’s work likewise engages with photography, combining postcard reproductions and found images from fashion magazines with rough hand dyed and printed cotton sheets. Hanging down against the wall, covered in irregularly repeating patterns of expressionistic smudges and splatters, the silkscreened fabric recalls the stained squalor of makeshift curtains, the drudgery and toil of domestic labor, as well as the space of the body and its residues. Juxtaposed with the abstraction of these marks, the images, fixed directly to the surface with tape, evoke the passionate yet provisional affinities of youth, such as those found in the decoration of adolescent bedrooms. Layered, but separate, never becoming one, the viewer is left to consider how these two features align, their dual intensities and contrasting modes of representation together touching on matters of desire and identity.

Lisa Anne Auerbach has called herself a “live meme.” Long before social media supplanted the physical bulletin board, Auerbach’s sweaters rendered her body a site for political messaging. The text and images in these sweaters are materially incorporated within the knitted object; this is not an additive process. Auerbach’s project hews closely to a history of knitting, in particular patterns popular in the 1970s like Fair Isle knits favored by the preppy set and traditional Norwegian Setesdal sweaters appropriated by the same, while also worn by Olympic athletes. If traditional Norwegian patterns were designed to ward off evil spirits maybe Auerbach’s sweaters carry some vestigial power to protect and possibly even to project something like hope. For Auerbach, “making things solidifies ideas….the translation from the haziness of consciousness into an object to be worn includes the manifestation of intention.”

Charles LeDray is known for his obsessive sartorial craftsmanship in the tailoring of tiny suits and uniforms. But garments are only one part of the countless miniature objects–tens of thousands–LeDray has crafted by hand. At first, due to the small scale of these works, the viewer may feel a sense of mastery over them, but that soon fades as one tries to make sense of the puzzle pieces laid out before them. Associations of masculinity suggested by the title Briefs could refer to men’s underwear or the brand of cigar once contained in the diminutive boxes. With their contents exposed, a beguiling and confusing portrait begins to take shape that complicates thoughts about gender. There are pin cushions, thread, lace, buttons, lava brand soap–a hyper masculine signifier–and odds and ends of paper fragments. What is the viewer to make of a small ad for a screening at Broadway and 46th St. of “Children of Loneliness” about “the third sex” or a partial clipping concerning “thought,” its dangers, its power and its value? The work requires seeing and reflection to decipher these curious analog bits.

Baxter Koziol takes on the burden of masculinity differently from LeDray by employing his own unique array of masculine signifiers. Both LeDray and Koziol were taught to sew by their mothers. Koziol stitches together discarded scraps of fabric to produce soft sculptural interpretations of hyper-masculine forms. In Mobile Command Unit (2024) the viewer is confronted with a work that conflates an instrument of war with a living room fixture–an armchair–embodying conflicting figures of masculinity: from military combatant to video gamer to dad with a beer in his La-Z-Boy. Koziol’s exploration of masculine excesses and expectations are inspired by literature, film and popular culture ranging from The Lord of the Flies to Robocop. His work often incorporates actual toys such as super-hero figurines to further complicate the ways that masculinity is performed and idealized.

The baby Yvonne is the eponymous character in Rosemarie Trockel’s video work Yvonne(1997), a playful moving image collage featuring a continuous parade of knitted garments situated within architecture, community, and popular culture. The video features a diverse cast of characters within a domestic context, reinforcing the intimate connections these knitted things have with the human body. In prior work from the 1980s, Trockel produced an edition of machine knitted balaclavas with familiar and abstract patterns that evoked conflicting ideas of protection and protest. Around the same time, Trockel made a series of “knitted paintings,” a medium associated with women and craft. Both process and material offered a critique of a male dominated art world that overvalued painting at the expense of other media. Trockel’s uncraftlike use of knitting is part of her conceptual breadth and uncategorizability.

According to Janice Redman“the act of making becomes a personal ritual, a process of revealing that which lies beneath the surface of the everyday.” She explains that she is from a family of makers; her mother was a seamstress and a lacemaker. Working with domestic objects with which she has an intimate connection, Redman manages to shift the familiar into the realm of the uncanny. In a work titled Ourobos (2018) a change purse opens up to suggest an endless cycle of thrift and expenditure, always empty, always in need. In Nestled(2021) a neatly stitched woolen bowl becomes the antithesis of the comfort hinted at in the title reminding us that home and family are always a negotiation between pain and relief. Not unlike Meret Oppenheim, familiar objects are turned into hallucinatory images both threatening and humorous.

The title of Marcelline Mandeng Nken’s Grandmère (2024) extends the theme of matrilineal relations in silent homage to Louise Bourgeois’ Mamanas well as Mandeng Nken’s own grandmother who taught her to sew. This outsized wooden needle, according to Mandeng Nken, “doubles as an elder’s staff, merging aspects of the maternal and the mechanical, as well as the domestic and the monstrous, into a singular, uncanny form.” The sculpture retains the defiant nature of wood revealing an occasional knot or irregularity which aids in perceiving it organically as the anatomy of a spider’s leg. Mandeng Nken goes on to explain that her sculpture “is not just a tool but also the body of a creature that weaves invisible architectures of care and capture.” Untitled (caryatid) will be performed during the opening, activating one of Victoria Fu and Matt Rich’s art objects.

Peter Coffin’s conceptual practice is shaped by West Coast Conceptualism and Funk art. Coffin explains that West Coast Conceptual artists did not abandon material, labor or craft, while East Coast Conceptual art was founded on the “dematerialization” of the art object. Although he did not make it, Coffin’s hot air balloon swatch is intended to extend the life of a beautifully designed object so that people can continue to enjoy it in a different context. Untitled (3D God’s Eye) is a model that defines Cartesian geometry and is configured within a tradition that derives from the popular American craft known as a “God’s Eye.” Coffin explains this work tweaks the familiar form while invoking nostalgia and craft. A “God’s Eye” is traditionally made of two crossed sticks with yarn that is wrapped from and around their center to form a diamond shape. Coffin will lead a workshop on September 21st (12-3PM) open to all ages in the making of 3-D God’s Eyes and God’s Eye glasses.

Elshu, a project of textile designer Lauren Frauenschuh, transforms knitwear into one-of-a-kind objects that speak to the truth of their making, celebrating the organic and painstaking process of placing each thread by hand. The minimalist design, made by tying strands of yarn on each re-purposed chair is reminiscent of the patterns in Rosemarie Trockel’s knitted paintings while also recalling utilitarian Bauhaus design. In the 1920s Bauhaus textile designer Gunta Stölzl wove upholstery fabric for tubular chairs similar to the ones made functional once more by Elshu. By transforming knitwear into a canvas for raw expression, Elshu invites the user or wearer to build on the intention and purpose of these works.

Elizabeth Duffy’s project involves unbraiding braided rugs made from fabric remnants no longer useful due to deterioration through wear. After unfurling and ironing each segment, Duffy then reassembles them, resulting in unexpected configurations. Wearing/Tent (2020) suggests shelter, but the domestic is turned inside out as the fabric spills back into small pools of the original braided rugs on the outside of the tent. In Wearing/Sentinels(2020), the tenderness of Duffy’s project is particularly present as ironing boards are covered with rug remnants made from women’s stockings. Traces of working women’s bodies are imprinted in the fabric through holes and repairs that were attempted time and again. These works, according to the artist, serve “to acknowledge the labor of anonymous women makers through time.”

Ruth Shafer explores the ways gender and class inform the bulk of domestic labor. Often rendered invisible, this labor is only perceived in its aftermath–a made bed, folded linens and clean laundry. Shafer pushes the viewer to think about the political implications of care, domesticity and the home. With Slipcover (2022), Shafer manifests an analogy in material form by merging the female figure with furniture. She explains, “furniture and the female body have a lot in common. Physically, there are arms, legs, a strong back and comfortable cushions to lean back on.” Slab (2024) according to Shafer “is both a tomb and an offering to those whose homes and bodies are no longer their own.” The rectangle of upholstery, reminiscent of a tombstone, a fallen beam, or detritus from a home destroyed in an unending cycle of warfare, collapses to reveal a ghostlike form just visible beneath the fabric.

Heidi Blunt’s work eschews the elegant formality of traditional tapestries. Rather than aristocratic hunting scenes or visions of unicorns, the viewer is confronted with a dingy bathroom strewn with dirty underpants–a room where we are at our most vulnerable. Blunt brings together found and rescued textiles in GRWM: Hirsute (2023), destabilizing the social media trend “Get Ready With Me” by demonstrating the strenuous efforts made to rid her face of an unwanted lady beard, an act once held in shameful secrecy. The work lifts the curtain on this private ritual, creating space for dialogue and freedom, while also exploring conflicted feelings about facial hair, identity, and the gender norms reinforced through its removal.

In Tomoe Tsutsumi’s performative work I want to fix your hole the artist humbly mends for the visitor a worn garment in need of repair. The hole and its repair return an object to usefulness in a gesture of care invoking Louise Bourgeois’ understanding of the needle. The visitors who participate are held in place for the time it takes Tsutsumi to examine the hole and then to mend it. Generating a conversation between the artist and the participant is the point of Tsutsumi’s work falling outside of the transactional discourse between tailor and customer. This work also subverts the discourse around art and its market. The final product is not simply a fixed garment, but also a work of abstract art that bears the handiwork of the artist in bold red thread. Lisa Anne Auerbach Heidi Blunt Peter Coffin Elizabeth Duffy Elshu Victoria Fu and Matt Rich Raisa Kabir Vicky Kim Baxter Koziol Charles LeDray Ziddi Msangi Marcelline Mandeng Nken Janice Redman Ruth Shafer Gwen Smith Rosemarie Trockel Tomoe Tsutsumi Alexis Zoto[i] Pandora Tabatabai Asbaghi and Jerry Gorovoy, Louise Bourgeois: Blue Days and Pink Days (Milan: Fondazione Prada, 1997) 218.[ii] https://gladstonegallery.com/exhibit/fake-it-fake-it-till-you-fake-it/