Nga Aurenc Bebja*, Francë – 14 Tetor 2023

“Il Piccolo di Trieste” ka botuar, të shtunën e 12 prillit 1913, në ballinë, përgjigjen e Isa Boletinit mbi arsyet se pse asokohe shqiptarët nuk kishin reaguar menjëherë ndaj pushtuesit serb, të cilën, Aurenc Bebja, nëpërmjet blogut të tij “Dars (Klos), Mat – Albania”, e ka sjellë për publikun shqiptar :

Pse shqiptarët nuk luftojnë kundër serbëve

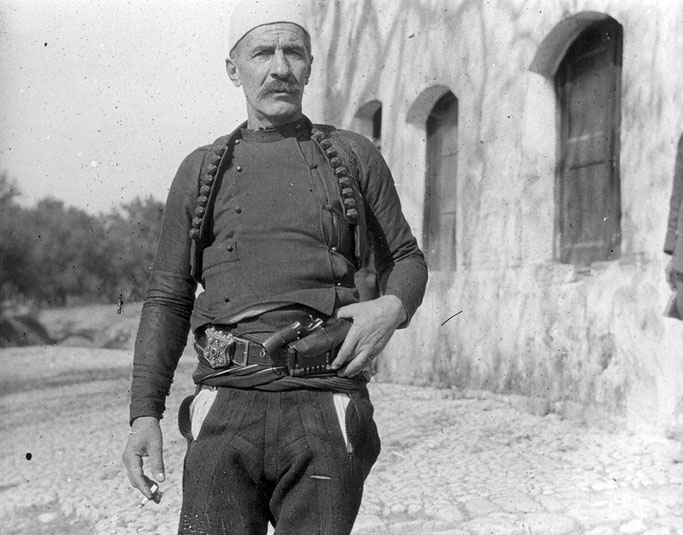

Vjenë 11, prill. Agjencia shqiptare publikoi si më poshtë deklaratat e Isa Boletinit, i cili erdhi në Vjenë nga Roma së bashku me Ismail Qemalin :

“Në Evropë përgjithësisht u habitën pse ne nuk e kundërshtuam pushtimin serb me armë në dorë. Arsyet janë këto : Lufta e vazhduar për dy vjet kundër xhonturqve na kishte lodhur. Xhonturqit na çarmatosën dhe na shkretuan fshatrat. Kur filloi lufta, serbët dhe malazezët na dërguan negociatorë, të cilët na siguruan se edhe aleatët ballkanikë do të luftojnë për lirinë dhe pavarësinë tonë. Ne besuam në ta, por ndërsa ishim të pafuqishëm, na sulmuan, shumë nga njerëzit tanë u vranë dhe ajo që mbeti nga prona jonë u shkatërrua dhe u vodh. Nuk mund të besoj se Evropa dëshiron t’i braktisë Serbisë qindra mijëra shqiptarë që jetojnë në Vilajetin e Kosovës; nuk do të ishte as në interesin e Evropës. Ne luftuam kundër sulltanit, tani do të luftojmë edhe kundër serbëve për të shpenguar veten nga këta shtypës.”