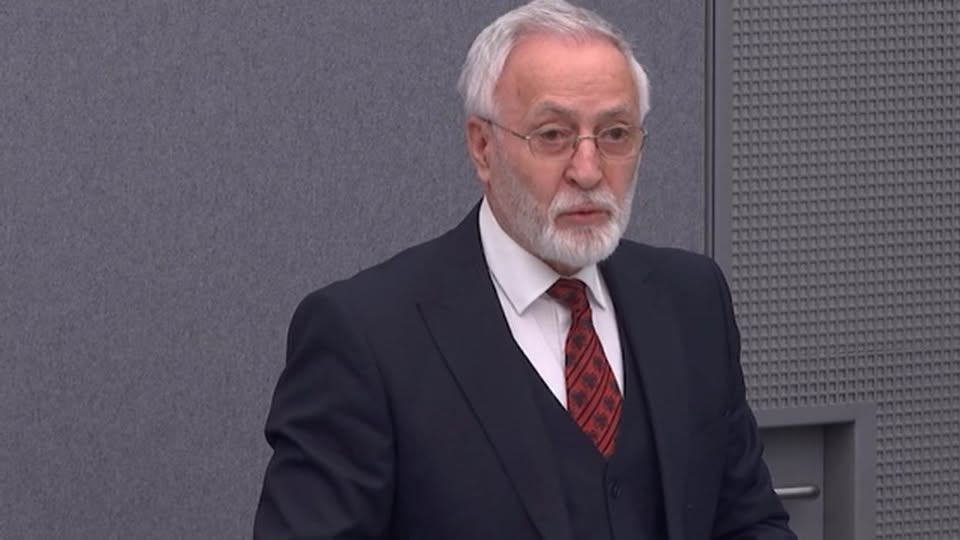

Prof.Myrvete & Prof.Begzad Baliu/

Dr. Jakup Krasniqi (Negrovc, Drenas. 1951), mësimdhënës, historian, publicist, pjesëtar aktiv i Lëvizjes Ilegale të Kosovës, zëdhënës i Ushtrisë Çlirimtare të Kosovës, shtetar i Republikës së Kosovës. Ky është profili atdhetar, intelektual, shkencor e shtetëror i studiuesit me të cilin po merremi në projektin tonë, me synim sintezën e veprës së tij shkencore.

Ai është autor i veprave me kërkimeve shkencore, polemika, sinteza e diskutime për çështje historike e aktuale të cilat shquhen për kërkimet dhe diskutimet e ideve të mëdha kombëtare, guximit qytetar të artikulimit të tyre në kohë shumë të vështira para gjykatave serbo-jugosllave, përmasën intelektuale të formësimit të tyre gjatë luftës për Kosovën dhe sidomos gjatë ndërtimit të shtetit të Kosovës etj.: Kthesa e madhe – Ushtria Çlirimtare e Kosovës (2006), Një luftë ndryshe për Kosovën (2007), Pavarësia si kompromis (2010), Lëvizja për Republikën e Kosovës 1981-1991 sipas shtypit shqiptar ( 2011) Guxo ta duash lirinë, (2011), Pranvera e lirisë ’81 (2011), Flijimi për lirinë (2011), Pavarësi dhe personalitete: në 100-vjetorin e Pavarësisë së Shqipërisë (2012), Një histori e kontestuar: kritikë librit të Oliver Jens Schmitt: “Kosova – histori e shkurtër e një treve qendrore ballkanike”, (2013), Zhurmuesit e demokracisë, (2015), Reflektime demokratike (2017, Skënderbeu dhe porositë për shekullin XXI (2018), Arti i bisedimeve (2018), Ballafaqime historike për çlirim e bashkim kombëtar (2019), Agresioni serb dhe taksa e Kosovës (2021) etj.

E parë në rrafshin diakronik të kërkimit, vepra e Dr. Jakup Krasniqit përfshinë: a. Periudhën Skënderbegiane, me theks të veçantë Skënderbeun dhe ndikimin e tij në formimin e identitetit shqiptar; b. Periudhën e Rilindjes Kombëtare e atë të Pavarësisë, me theks të veçantë bardët e këtyre proceseve; c. Periudhën e Lëvizjes Ilegale të Kosovës në gjysmën e dytë të shekullit XX me theks të veçantë Frymën Demaçiane, e cila i ka projektuar, përgatitur dhe udhëhequr këto procese deri te Shpallja e Pavarësisë së Kosovës; d. Periudhën e shtetndërtimit të Republikës së Kosovës, duke përfshirë këtu edhe sfidat me Gjykatën Speciale etj.

E parë në kontekstin tematik, vepra e Dr. Jakup Krasniqit trajton përmasën historike të ndërndikimit të periudhave historike dhe personaliteteve të kësaj kohe nga njëra epokë në tjetrën, raportet Lindje-Perëndim dhe vendin e shqiptarëve në histori; konfliktet historike serbo-shqiptare dhe Kosovën si hapësirë mitike (serbe), etnike, historike e kombëtare shqiptare; Shpalljen e Republikës dhe raportet me bashkësinë ndërkombëtare; shtetndërtimin e Republikës dhe qëndrimin kritik ndaj zhvillimeve të kohës.

E parë në kontekstin shkencor të krijimit, vepra kërkimore, intelektuale e politike e Dr. Jakup Krasniqit, nuk shquhet për kërkimet historike arkivore (për shkak të burgjeve të gjata, jetës ilegale, luftës, angazhimit të drejtpërdrejtë në shtetndërtimin e Kosovës), por shquhet për sintezat e mëdha historike e politike, të çliruara nga ndikimi politik, institucional e ideologjik i kohës (nga të cilat nuk janë çliruar veprat shkencore të bashkëkohësve të tij para rënies së komunizmit), si dhe për sintezat intelektuale përtej ndikimeve partiake, ideologjike e klanore, prej të cilave nuk janë liruar pjesa më e madhe e veprave shkencore të shkruara pas Luftës së Kosovës.

(Hyrje një një sintezë të mendimit atdhetar, shkencor, intelektual, kulturor e shtetndërtues në veprat e dr. Jakup Krasniqit)