Përktheu Rafael Floqi

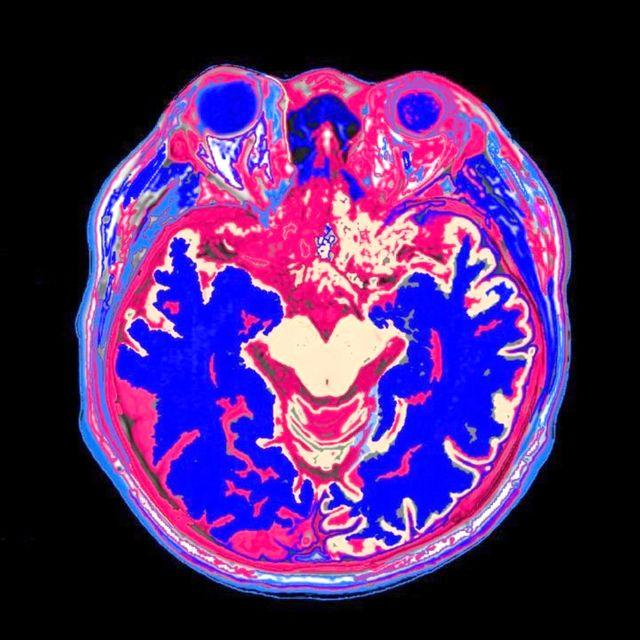

Shkencëtarët mendojnë se së shpejti mund të shërojnë dëmtimet e trurit nga një goditje në tru. Studiuesit që induktuan goditje në tru te minjtë dhe më pas transplantuan qeliza staminale nervore njerëzore në trurin e tyre zbuluan se neuronet dhe enët e gjakut u rigjeneruan.

Pasojat e një goditjeje në tru mund të jenë katastrofike. Në varësi të kohës që truri mbetet pa oksigjen dhe lëndë ushqyese për shkak të ndërprerjes së qarkullimit të gjakut, komplikimet mund të variojnë nga humbja e kujtesës deri te dëmtimi i të folurit dhe madje edhe paraliza. Disa pacientë shërohen, ndërsa të tjerë jetojnë me dëme të përhershme — rreth gjysma e të mbijetuarve nga goditja në tru mbeten të paaftë për shkak të dëmtimit të trurit. Tani, transplantet me qeliza staminale mund të jenë një ditë në gjendje të kthejnë pas dëmet që deri tani konsideroheshin të pakthyeshme.

Neuroshkencëtarët Christian Tackenberg (nga Universiteti i Cyrihut) dhe Ruslan Rust (nga Universiteti i Kalifornisë Jugore) bashkëpunuan për të eksploruar një terapi të mundshme që përdor qeliza staminale pluripotente — të cilat mund të shndërrohen në pothuajse çdo lloj indi — për të trajtuar simptomat që mbesin pas një goditjeje në tru. Ata induktuan goditje në tru te disa minj dhe transplantuan qeliza staminale nervore njerëzore në trurin e tyre, duke treguar se këto qeliza kanë potencialin për të krijuar neurone të reja dhe për të aktivizuar procese të tjera rigjeneruese.

“Qelizat staminale nervore] mbijetojnë për më shumë se pesë javë, diferencohen kryesisht në neurone të pjekura dhe kontribuojnë në reagime të indeve të lidhura me rigjenerimin, duke përfshirë angiogjenezën, riparimin e barrierës gjak–tru, uljen e inflamacionit dhe neurogjenesën,” shkruan Tackenberg dhe Rust në një studim të publikuar së fundmi në revistën Nature Communications.

Çfarë lloj goditjeje u përdor në eksperiment?

Ekzistojnë dy lloje kryesore të goditjeve në tru:

- Ishemike, që ndodh kur një arterie që çon gjak në tru bllokohet (zakonisht nga një mpiksje gjaku për shkak të akumulimit të pllakave),

- dhe hemorragjike, që ndodh kur një enë gjaku çahet dhe gjaku rrjedh në indet përreth, duke rritur presionin në tru.

Studiuesit zgjodhën të induktonin goditje iskemike te minjtë, pasi ato janë shumë më të zakonshme te njerëzit — rreth 1 në 4 të rritur përjeton një goditje iskemike gjatë jetës.

Si u zhvillua eksperimenti?

Pas një jave nga goditja, minjtë — të cilët ishin gjenetikisht modifikuar që trupi i tyre të pranonte qeliza njerëzore — morën transplant me qeliza staminale nervore njerëzore në zonat e dëmtuara të trurit. Goditja kishte shkaktuar reduktim të madh të qarkullimit të gjakut, dëmtim të indeve dhe dobësi motorike.

Menjëherë pas trajtimit, lezionet (dëmtimet) filluan të zvogëloheshin pak. Përparimi i qelizave të transplantuara u monitorua me anë të imazherisë biolumineshente. Duheshin dy javë që sinjalet ndriçuese të fillonin të rriteshin — gjë që sugjeron se trurit i dëmtuar i duhet kohë për t’u stabilizuar përpara se trajtimi të funksionojë plotësisht.

Rezultatet ishin të jashtëzakonshme

- Inflamacioni u ul.

- U gjeneruan neurone të reja, të cilat komunikonin me neuronet ekzistuese.

- Zgjerimet neuronale (neuritet) arritën në:

- Korteksin motorik (kontrollon lëvizjet vullnetare),

- Korteksin somatosensor (përpunon ndjesi si prekja, presioni, dhimbja),

- dhe korteksin cingulat, që luan rol në:

- marrjen e vendimeve,

- kujtesën punuese,

- formulimin e përgjigjeve,

- dhe kryerjen e detyrave.

Por përmirësimet nuk u kufizuan vetëm te qelizat e trurit. Transplanti ndihmoi edhe në rigjenerimin e qelizave që formojnë enët e gjakut.

Në mënyrë interesante, rrjedhja nga enët e reja të gjakut ishte më e vogël — ndryshe nga zakonisht, pasi enët e reja pas goditjes priren të jenë më të brishta dhe rrjedhëse, gjë që mund të ulë në mënyrë të rrezikshme presionin e gjakut.

Si rezultat i rigjenerimit të trurit, aftësitë motorike të minjve u përmirësuan.

“Këto zbulime mund të kenë rëndësi jo vetëm për terapinë e goditjeve në tru, por edhe për trajtime të një game më të gjerë të dëmtimeve neurologjike akute që përfshijnë humbje të neuroneve,” shkruajnë Rust dhe Tackenberg.

A është kjo terapi e zbatueshme për njerëzit?

Ende nuk janë bërë prova klinike të qelizave staminale nervore te njerëzit për këtë lloj trajtimi.

Por ka aspekte të terapisë që mund të përshtaten për përdorim te njerëzit.

Studiuesit tani po kërkojnë mënyra më të thjeshta për dorëzimin e qelizave, si për shembull:

- injeksione, në vend të transplantimeve më invazive që u përdorën te minjtë.

E ardhmja: jo vetëm mbijetese — por rimëkëmbje dhe mirëqenie

Në një të ardhme të afërt, mund të jetë e mundur jo vetëm të mbijetosh nga një goditje në tru, por edhe të rikuperohesh plotësisht dhe të lulëzosh, falë fuqisë së qelizave staminale. Dhe keshtu mallkimi “të raftë damllaja!” do të jetë pa kuptim.