Case Study: MOTHER TERESA

Dr. Etleva Lala

On 9-10 June 2022, the Albanian Studies Program at the Eötvös Loránd University (ELTE BTK), Budapest and the Embassy of the Republic of Albania in Hungary organized the International Conference “Saints as Promoters of Good Neighborliness: Case study: Mother Teresa”, with a keynote lecture by the well-known scholar of Mother Teresa, Prof. Dr. Ines Murzaku, who is Professor of Religion, Chair and Director of Catholic Studies Department and Program at Seton Hall University and International Federation of Catholic Universities and also Head of Catholic Studies International Group.

Saints are often celebrated beyond their national, territorial, political, and even religious borders, becoming living examples of how to love others and how to promote neighborliness, even and especially when such neighborliness seems to be impossible for human nature. Nevertheless, this is still a field of research, which has not attracted much scholarly attention in the Balkans. Studying Mother Teresa as a case study, who was born and grew up not only in times of turmoil, but also in a region where people who had ethnic, religious, economic, cultural, and educational differences were clashing in the most extreme ways, is an attempt to approach such a topic from the scholarly perspective. The power of a saint is most often shown in these times and places of turmoil, as the saint brings peace. Particularly, devotion to saints who lived in areas of conflict is known to encourage unity and peace. In this conference, we aimed at displaying how Mother Teresa unites the world through her love for humanity. By highlighting as much as possible her uniting and peace-bringing spirit, we explored not only how a person may change the world, but also how people unite and interact around the saints, improving their relations with one another.

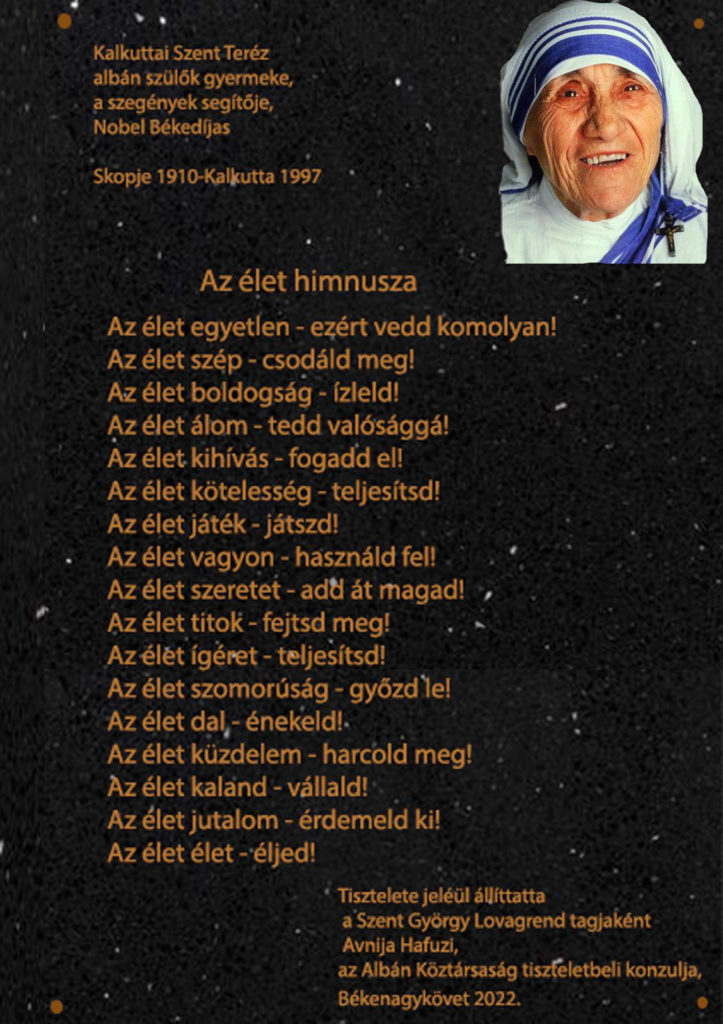

On the first day of the conference, 9 June 2022, at 10:00, the participants of the event were greeted warmly by Ms. Gentiana Mburimi, Charge d’Affaire of the Republic of Albania in Hungary and H.E. Ms. Gjeneza Budima, ambassador of the Republic of Kosovo in Hungary. Mr. Avni Hafuzi, Honorary Consul of the Republic of Albania in Pécs, Hungary, supported the conference with the necessary logistics during the coffee breaks, making it pleasant for the participants to continue their presentations and discussions. Mr. Hafuzi also displayed some of near future plans on this occasion, the most relevant of which is the placement of two commemorative plates with the hymn of Mother Teresa in two Hungarian cities: Pécs and Ajka.

The plenary speech of Prof. Dr. Ines Murzaku, titled “Balkan Women: Nurturers of Mother Theresa’s Revolution of Tenderness”, offered a deep insight into how Mother Teresa can be approached not only as a saint, but also as a Balkan woman, who was nurtured by the local tradition and turned that tradition into a universal one. She focused especially on the revolution of tenderness, who changed the world not through power and violence, but through little gestures done with great love, like smiling five times a day, not only who are perceived as ‘nice’, but especially to the other ones. This panel lecture of Prof. Dr. Murzaku reflects a lot from her book “Mother Teresa, Saint of the Peripheries”, published by Paulist Press (New York/ Mahwah, NJ) in 2021.

The Academician Shaban Sinani, from the Academy of Sciences of Albania sent his paper: Some data about the Fatherland of Mother Teresa. In his contribution, acad. Sinani focused on the visits of Mother Teresa in Albania in the late 1980s. Her first visits have been rightly rumored, he states, as if Mother Teresa were not well received, and were not given the reserved honors she deserved. In all these, there are partial truths, according to acad. Sinani. The very fact, however, that Mother Teresa did not interrupt her visits to Albania since 1989, shows that her contacts were stable. When it comes to the sources, they show that the visits of Mother Teresa in Albania and the attitude of state authorities of the time have changed for the better. This is also reflected by the expression of the decision of these authorities to offer the Albanian state passport to Mother Teresa. This was certainly not an easy task in the Communist Albania, although for Mother Teresa it was almost a routine to get passports: in addition to the Italian, Vatican, British and Indian passports, she also had an American passport. Meanwhile, the Albanian state, for almost half a century, had rejected it to her, as well as the entrance to the land where the graves of her parents and family members were to be found.

In early 1991, the former President Ramiz Alia initiated the first attempt to obtain the necessary information, whether Mother Teresa would accept the granting of an Albanian passport to her. For this mission, the state authorities of the time, sought the help of the Christian community of San Egidio, who had confidential relations with Mother Teresa, in order that in the case Mother Teresa would reject it, that would remain only an orally addressed issue. As expected, Mother Teresa did not object the reception of the Albanian passport, but on the contrary, she immediately confirmed its acceptance. Since the establishment of the Order of Mother Teresa in Albania seemed almost impossible at that time, it was decided to hand the passport over to Italy, counting always on the mediation and support of the San Egidio’s community.

Since 1991, thus, Mother Teresa had officially an Albanian passport, in addition to the other passports mentioned already, which were not accidental: Vatican and Italian passports were associated with the center of Western Christianity, around which the mission of Mother Teresa’s Order operated. The British passport was bound with her relatively long stay for schooling and training, up to entering the path of the mission of charity and humanism. The passport of India was connected to the capital of her service. American passport was the expression of her global dimension as a personality. The Albanian passport expressed the relationship with the land of her ancestors.

Accepting a passport, in legal terms, means accepting citizenship of the country that issued it, just as the issuance of a passport is a legal act, which has to do with the recognition of citizenship and the obligation of protection of citizenship. Mother Teresa was given a diplomatic passport by the Albanian authorities, the highest degree of official state identification. All these actions have certainly left their mark on the written practice of the main institution of the Albanian state and its consular services. We do not know, if Mother Teresa had a chance to use the passport of the Albanian state. It is well known the fact that she had no need for that passport at all when she entered Albania. The decision to accept it, however, was a decision to express a specific relationship with Albania.

In the afternoon session, Arben Arifi, a scholar from Kosovo, who also teaches at the University of Prishtina, spoke about The influence of the Albanian tradition in the formation of Mother Teresa. Born in Skopje, into an Albanian Catholic family, Mother Teresa was faced with extremes of social levels among the rich and the poor since her childhood. The solidarity, humanity and charity, prevailing among the Albanians, was according to Arifi, what paved her journey since childhood. The Albanian tradition from which Mother Teresa came, as her parents were both coming from the territories of present-day Kosovo, shows that she herself is the most modern example of that devotion that came from the Albanian Christian tradition with apostolic roots.

In the question session, there was a debate about the origin of the parents of Mother Teresa. It is already a well-established fact that the father of Mother Teresa came from Prizren, but whether the mother of Mother Teresa originated from Bishtazhin or Novosello, at the municipality of Gjakovo in Kosovo, that is sometimes questionable.

Musa Ahmeti, Researcher at the Center for Albanian Studies, Budapest, talked about some letters of Mother Teresa, which shed light on the first visit of Mother Theresa in Albania. The procès-verbal of the first visit of Mother Teresa was extremely interesting, as it documented all that was done in this visit. The letters were given to Dr. Ahmeti by Kolec Çefa, an Albanian scholar, who has a rich archive in Catholic sources during Communism and in the years after the fall of Communism. Most of these sources are now housed at the archive and library of the Franciscan Order in Shkodra. These letters shed light on how Mother Teresa was received by the president Ramiz Alia on her first visit, and how she paved the way for religious tolerance in Albania. It is interesting to see that she Mother Teresa was not only confident in receiving what she was asking for, namely houses for her sisters in Albania, but she was also suggesting a new way of thinking to a society, which considered religion as a sacrilege.

Sokol Paja, Chief Editor of the Oldest Albanian Newspaper in the USA “Dielli/The Sun”, presented (through Paulin Marku) a paper about the visits of Mother Teresa in Albania according to the oldest Albanian Newspaper “Dielli/The Sun”. In this paper, we were not only informed about all the cases, when Dielli reported about Mother Teresa in general, but also offered an analysis on how these reports boosted the identity of the Albanians in the USA, by regularly showing the origin of Mother Teresa and how she related to the Albanians.

Anthony Nicotera, JD, DSW, LSW, Assistant Professor at Seton Hall University and director of NYU’s PostMaster’s Certificate Program in Spirituality and Social Work, presented paper titled “Where is the Love? Mother Teresa and Seton Hall University’s Catholic Social Thought in Action Academy.” In his contribution he utilized concepts developed by him like ‘the See, Reflect, Act Circle of Insight process’ as a tool for exploring lessons learned about love and good neighborliness from time spent living and working in Calcutta with Saint Mother Teresa and the Missionaries of Charity. His interest about this topic, started during his time in Calcutta, when Mother Teresa asked him “Where is the love?” Inspired by this question, Dr. Nicotera, in collaboration with Drs. Dawn Apgar and Ines Murzaku, cofounded Seton Hall University’s Catholic Social Thought in Action Academy, at the intersection of Catholic Studies and Social Work, which seeks to promote a spirituality of love and service, centering those on the periphery, consistent with Mother Teresa’s insights and sacred, prophetic witness.

The commitment and vision of the Academy beckons us to see, in the words of Mother Teresa, “if we have no peace, it is because we have forgotten that we belong to each other.” Through service, research, teaching, conversation, workshops and conferences, the Academy challenges students, and its community to embrace the inherent dignity and interconnectedness of all human persons, all life. In the spirit of Mother Teresa, the Academy calls to a pedagogy and practice of holiness, belonging, beloved community, interbeing, revolutionary love, and a spiritually sensitive, socially just, transformative social work practice, which is developed also by scholars like Murzaku (2021; Teresa, 1997, 2007), Dr. King (2000), Thich Nhat Hanh (1993, 2014), and Valerie Kaur (2020), Canda, (2020), Dudley (2016), Nicotera (2019, 2022), Pyles (2018).

Asked whether he was influenced by Paulo Freire and his Pedagogy of the Oppressed, Dr.Nicotera confirmed that Freire’s work had been a seminal work to his research and work as an educator and activist, but certainly upgraded through the Catholic philosophy of Mother Teresa.

Etleva Lala, head of the Albanian Studies Program, ELTE University, Budapest, talked about Mother Teresa’s Way of Neighboring vs. Traditional Neighborhood in the Balkans. In the beginning, she talked about her experience with sources of the Holy Penitentiary in the Vatican Secret Archive and how the Holy Penitentiary created a Christian culture in the Catholic West, where public forgiveness and public positive and purposeful forgetfulness are institutionalized in such a way, that the individual cannot use his feelings to act on the common peace and culture of the community.

The Holy Penitentiary, Sacra Penitentiaria Apostolica (SPA) emerged in the twelfth century and was par excellence the instrument by which the Pope bestowed grace. The task of SPA was to adjudicate petitions of those who had in any way transgressed religious-canonic norms and eventually pardon them. At the beginning, only those wishing to enter or preserve clerical status applied to the SPA, seeking to amend some irregularity (illegitimate birth, physical defects, etc.) or to atone for a crime, or to receive a benefice (alleviation of fasting, permission to change monastic order, etc.). Gradually, however, the competence of the SPA grew so as to deal with all social groups and various kinds of transgressions. The task of the SPA was formulated as “the provision of medicine and remedy for sins,” and since almost any deviation or misconduct in the Middle Ages was perceived as a sin, by the mid-sixteenth century the SPA possessed nearly universal juridical competence.

The reason why the Holy Penitentiary is mentioned in the Balkan context, is that Mother Teresa came from a Catholic Christian tradition and she could compare the impact public forgiveness and forgetfulness had onto the social life of the Western Christianity and especially onto the neighborhood. By taking over the responsibility to handle conflicts and crimes, the Holy Penitentiary offered redemption to the whole society, because after being absolved from the Holy Penitentiary, crimes could be forgiven and forgotten not only in heaven, but most importantly in the neighborhood. Upon receiving absolution from the Holy Penitentiary, nobody was allowed to bring up the forgiven sin/ crime, because that was already dealt with and no person is higher than God, whose representative, in this case, was the Holy Penitentiary.

In the Eastern Church there was no institution which would replace the Holy Penitentiary, in the sense that it offers absolution for committed sins and crimes and redemption not only to the sinner/criminal, but to the whole society. The Eastern Orthodox Church does not have the institutional power to forgive publically a crime, but only to condemn it and to distance itself from it. The individual who commits a crime is, thus, not only condemned officially by the ruling authorities, and with a bad reputation culturally, but also unofficially, by the victim’s family and network, who take the matter on their hands and seek revenge. The memory of the criminal continued and continues to live not only in the present generation, but is transmitted to the next generations, making it a poisoned tradition of hatred and judgment. These old memories create a neighborhood, which is never as reliable as one would like it to be.

Not being able to know or to predict the attitude of the neighbors, whose distant past may be unknown, creates a background of distrust in connecting to them, which shows up especially in times of crises and/or wars. Most of the time, it is the neighbor, who is reported to be alienated without a visible or understandable reason and who acts more violently and aggressively than the others, and when asked about this behavior, they report old histories coming from previous or ancient generations. Even if the crime was committed unwillingly and the criminal had repented, there was no way of undoing it and escaping the consequences for the whole family and future generations.

Besides the Christian (Catholic and Orthodox) communities, Skopje had and continues to have a huge Muslim community. When talking about crime and neighborhood, the Muslim religion has introduced the sacrifice of a lamb and of other material goods, or even a trip to Mecca as a way of redemption from the sins. The bigger the sin, the higher the material sacrifice they have to pay, but to some certain extent that brings redemption to the society also. The memory of the sin, however, remains in the community and is a basis for mistrust.

If we consider a vertical analysis in the history of the Muslim conversion, at least in the Balkans, another element of distrust may be added to the Muslim communities, seen from the perspective of Christian neighbors. The Ottoman rule did not force a Muslim conversion as it was done in the West through the moto “Cuius regio, eius religio”. In the beginning, the Muslim rule gave freedom to the individual to stay Christian and pay taxes or convert and live tax-free. For that reason, those who converted to Muslim religion fell into two categories from the perspective of the Orthodox Christians: If the individuals had the means to pay the taxes, but still preferred to convert in order to profit more privileges, they fell into that group, which was considered as drifters and opportunists. The other group, which did not have the means and choose to convert, because that was the only way to survive materially, did not enjoy a better reputation either, because poverty was considered a spiritual deficiency, made visible through this state of being. Being poor was not a virtue either, as it was transformed in the West, mainly by Mendicant orders.

Besides the orthodox Muslims, in Skopje there were also the Bektashis, a Muslim sect, which is not accepted by the Muslim religion. Bektashis introduced a different dimension of religious perception of the individual, namely that: “The good and the bad exist within each of us.” While all the other religions fight the bad in every person and try to make people distant themselves not only from the bad as a concept, but also from the person, who has exhibited a sign of badness in him/herself, the Bektashis’ progressive understanding of the bad and the good as existing in every human being as two inseparable parts of everything that exists, brings to a large extent a relaxation to the tense neighborhood. Everybody is a potential criminal, according to the Bektashis, because the bad exists already in each of us. This new perception offers a great tolerance for the otherness not only within the Bektashi communities, but to the whole Albanian community, as the Bektashis became the leaders of the national movement in Albania, promoting “Albanianism” above any religion.

Mother Teresa, thus, grown up in such a milieu, as Skopje was a multicultural city, with various ethnic and religious populations, was early introduced to such a neighborhood, poisoned by all the above-mentioned Weltanschaungen. The proud rich Orthodox (remember that they had been paying taxes to the Ottoman rulers in order to survive as Orthodox) looked down to the poor Muslims, who either because of poverty of because of greed, had changed religion and thus represented no good neighbors to the Orthodox Christians. On the other hand, nomen est omen and Orthodox meaning right, represented the drive of the Orthodox religious to be as right as possible in order to feel accepted by God, hence avoiding sinners was a must for them. Catholic, on the other hand, meaning universal, was a drive to reach the world for Christ, and not to avoid it. Hence the Catholics have developed so many social approaches, which in extreme cases went as far as to Holy wars and missionary conquests.

Mother Tereza was certainly faced very early in her life with all these contradictions within her relatively small city. She was probably not conscious of the roots of these opposing forces, as presented above, but she was definitely aware of their existence as the situation was and is still visible nowadays in Skopje. If in her prayers, she wanted to know her place in this world, following Jesus was obviously the answer of all her prayers, as that would become visible in her actions. Jesus changed the way people related to God and to each-other, creating different values, and so did Mother Teresa. She understood that it is family and neighborhood the starting point of a society and she started implementing her mission there with what she was given.

The new neighborhood Mother Teresa promoted was totally based on the image of Jesus. Jesus washed the feet of the disciples, humbling himself to people, who otherwise considered themselves unimportant and so did Mother Teresa. Mother Teresa humbled herself to unknown and unimportant people, by serving their terrestrial bodies, while touching, serving and treating them. As a provider, Jesus offered food to the hungry (fish, bread, wine), and so did the Mother: she provided food to the hungry. Jesus did not feed only the terrestrial bodies with material food, but also their souls: he gave peace to the frightened in the storm, to the worried about the future, to the greedy, to the sick, to the weak and so did Mother Teresa: besides the material goods, she also had a word of encouragement, which is still valid for each of us today and also for her sisters. What is more important, Mother Teresa used to think out of box, just like Jesus did: Jesus did unorthodox things, which shocked the world around him: not only did he talk to a Samaritan woman, to a prostitute, to a tax-collector and made himself dirty by the woman, who touched him in order to get healing for her issue, but he desacralized the Sabbath by ‘working’ on that day, and put mud or other dirty material onto the blind eyes of poor men. Mother Teresa was also very bold and courageous, by being radical in many ways, not fearing any secular powers, but only God.

On the morning of Friday, 10 June 2022, the conference started with a round table discussion with Mother Teresa’s Sisters in Budapest, led by Bilung Mary Romana MC Leader sister and moderated by Prof. Dr. Ines Murzaku and Dr. Etleva Lala. It was a unique experience to have such a wise and peace-bringing people at the spot, not only narrating about their life-style and mission as Sisters of Mother Teresa, sharing also personal experiences with Mother Teresa herself, but also displaying a profound wisdom generated by the rule, which goes beyond religious differences and restores the human dignity in a divine way. They showed examples of how they treat people in need without burdening them with religious teachings, restoring them physically and spiritually to the best version of themselves and yet at the same time letting them religiously freedom of choice. The conference participants had the chance to ask questions and even to share personal experiences which related to the social, religious, ethnic, economic or other differences that the Sister of Mother Teresa, just like her, were challenged to face in the daily life.

Besnik Rraci and Sadik Krasniqi, who work at the State Muzeum of Kosovo, followed up very nicely the contribution of the Sisters in the society. The Contribution of “Mother Teresa” humanitarian association during the years 1990-1999 in Kosovo, displayed the same spirit that the Sisters had reported in the morning. The ‘Mother Teresa’ humanitarian association, which had operated in 1990-1999 in Kosovo and beyond, had become extremely influential and widespread among Albanians in Kosovo and abroad, just because it approached individuals without considering their religious background. Albanians in Kosovo profited greatly from the services offered voluntarily by various professionals inside and outside Kosovo and also from the huge amounts of money collected from Albanians abroad and the system was so well organized and documented that absolutely no abuse was ever recorded or even rumored about this association.

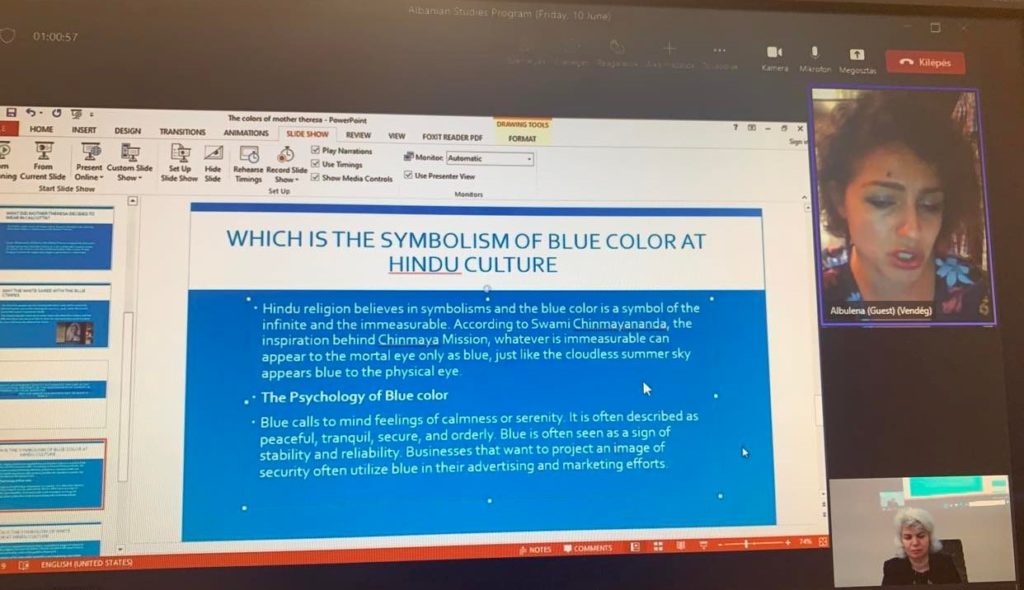

The only Ph.D. candidate we had in this conference, Albulena Bilalli, spoke about The Colors of Mother Teresa, presenting them from a scientific point of view, as she is a scientist of colors and light, working on the effect various colors have on the psychology of the individuals. How the colors of the dress of Mother Teresa were chosen, the effect they have, the tradition they follow and how they got institutionalized as a distinct symbol of a great mission, were only some of the questions she approached in her presentation and we look forward to have her paper in a publishable form, where she will also respond to questions, whether covering the head with a white kerchief is a continuation of the Albanian habit of the old women and men in Mother Teresa’s case.

In conclusion, we discussed the ways, how religious subjects, like saints, and the relation of the people in the Western Balkans to supernatural can become an object of scholarly debate and be treated in a scholarly way, for the purpose of shedding light into that aspect of the local culture, which was always part of the human being. The rejection of religious subjects is so extreme in the Albanian historiography: even medieval sources are rejected on that basis, as it is often the case with the Statutes of the Cathedral Chapter of Drishti. Opening the scholarly debate where the religious element should be part of the scholarly discourse, is certainly a long way, but since there are so many good examples to follow from the existing scholarship, it is not an impossible mission either.