Mid’hat Frashëri: Nëse Enver Hoxha heq dorë nga revolucioni socialist, Ballistët me kënaqësi do të luftojnë prapë kundër gjermanëve/

Nga SKËNDER BUÇPAPAJ/

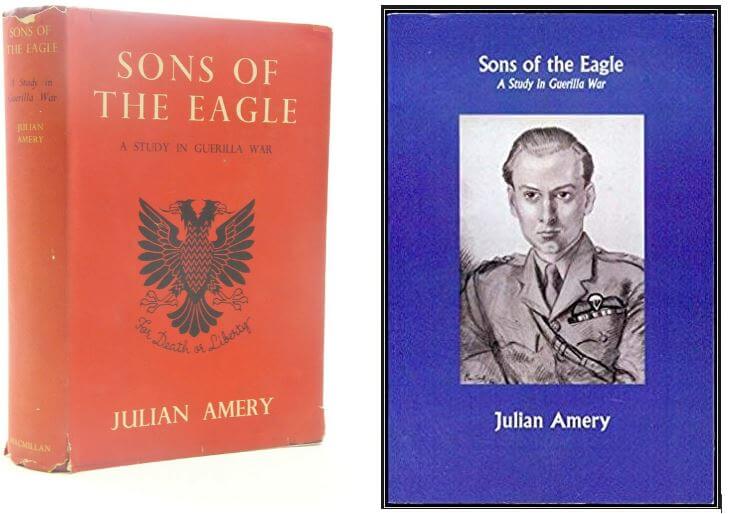

Për Mid’had Frashërin i shkruaj këto radhë me fjalët e një prej bashkëbiseduesve të tij më të shquar dhe më të paanshëm. Në faqet 183, 184, 185 të librit të tij “Sons of Eagle: A Study in Guerila War” (Bijtë e shqipes: një studim për luftën guerile), publikuar nga shtëpia botuese Macmillan, (botim i parë, 1948) Julian Amery përqëndrohet kryesisht te kjo figurë e historisë së re të shqiptarëve.

Kush është Julian Amery?

Midis viteve 1950-1992 Julian Amery ishte anëtar i Parlamentit Britanik 39 vjet. Ai ka mbajtur tri poste ministeriale: Ministër i Punëve Publike (1970), Ministër për Strehim dhe Ndërtim (1970–72) dhe Ministër Shteti për çështjet e Jashtme dhe Komonuelthin (1972–74).

Përpara Luftës së Dytë Botërore, Amery ishte korrespondent në Luftën Civile Spanjolle dhe më vonë atashe për Zyrën e Jashtme Britanike në Beograd. Pas fillimit të luftës ai iu bashkua Forcave Ajrore Britanike më 1940 si toger u transferua më 1941 në Ushtrinë Britanike, duke arritur gradën e kapitenit. Më 1941-1942 ai shërbeu në Lindjen e Mesme, Maltë e Jugosllavi dhe në Lëvizjen Shqiptare të Rezistencës më 1943-1944 (ishte një nga të ashtuquajturit “Tre mosketjerët” me majorin David Smiley dhe nënkolonelin Neil McLean). Në vitet e pasluftës Amery u bë mik i ngushtë i Mbretit Zog të Shqipërisë dhe në autbiografinë e botuar më 1973 e përshkruan atë si “burrin më të zgjuar që unë kam njohur”.

Amery besonte se një ndërhyrje e aleatëve mund të parandalonte marrjen e pushtetit nga komunistët kur shkoi në Shqipëri me McLean dhe Smiley në prill 1944. Por eprorët e tyre nuk pranuan dhe ata u detyruan të braktisin misionin e tyre. Ai nuk hoqi dorë nga ideja e ndërhyrjes për largimin e komunistëve nga pushteti në Shqipër as pas Luftës së Dytë Botërore.

Njohja me Mid’hat Frashërin

Amery tregon se me kreun e Ballit Kombëtar, britanikët u takuan tek shtëpia e Ihsan bej Toptanit. “Mid’hat Beu ka qenë zyrtar i Portës së Lartë, anëtar i Komitetit për Union dhe Progres dhe një figurë me ndikim të fuqishëm në përpjekjet e hershme për ndërtimin e shtetit shqiptar. Ai u tërhoq nga jeta publike gjatë monarkisë, sepse ishte një republikan me bindje të forta dhe iu përkushtua librarisë së tij. I formuar me kulturën e Evropës dhe të Lindjes së Afërme, ai ishte një njeri i sjelljeve të përkora, një konservator romantik, i përfshirë nga zjarri patriotik dhe nga një besim Katonian ndaj virtyteve të aristokracisë. Tash një mbi shtatëdhjetëvjeçar ai është një figurë trupdrejtë dhe i hequr me tipare ende të dukshme dhe me një lëkurë si pergamen. Në shikim të parë ai dukej pazakonshëm ngurues dhe se vuante nga mbajtja e gojës. Ai ishte i pajisur, megjithatë me një mendje të ftohtë por të ndritshme dhe biseda ishte tërheqëse dhe fitoi admirimin tonë. (Midhat Bey had been in turn an official of the Sublime Porte, a member of the Committee of Union and Progress, and a powerful. influence in the early struggles of the Albanian state. He had retired from public life under the monarchy, for he was a strong Republican, and since then had eked out his living from the proceeds of a bookshop. Steeped in the cultures of Europe and of the Near East, he was a man of austere ways, a romantic conservative, possessed of burning patriotism and a Catonian faith in the virtues of aristocracy. Now over seventy years old, he was a spare, straight figure, with determined yet sensitive features and a skin like parchment. On first acquaintance he seemed inordinately shy and was afflicted with a slight stutter. He vas gifted, however, with a dry but sparkling wit, and his talk at dinner that night assured our entertainment and compelled our admiration.)

Mid’hat Frashëri: Një revolucion komunist po përparon në Shqipërinë e Jugut kundër Ballit Kombëtar

Më tej, Amery shkruan për bisedën që patën britanikët me kreun e Ballit Kombëtar. “Kur darka mbaroi, ne u kthyem tek temat kryesore. Ne e akuzuam troç Ballin Kombëtar për “bashkëpunim” me gjermanët dhe kërcënuam se do ta denocojmë lëvizjen dhe udhëheqësit e saj si armiq të Aleatëve nëse ata nuk i braktisin menjëherë luftimet e tyre kundër partizanëve. Mid’hat bej ishte tejet i ndershëm për të mos u shtirur dhe u përgjigj se tash ishte tepër vonë. Një revolucion po përparon në Shqipërinë e Jugut, në të cilin komunistët, janë të organizuar nga Lëvizja Nacional Çlirimtare, me qëllim që të shthurin rendin social të mbrojtur nga Balli Kombëtar. Të dyja lëvizjet e kanë zanafillën në rezistencën ndaj italianëve, dhe në Mukje, më 1943, kishin arritur një aleancë për veprime të përbashkëta kundër ushtrive të Aksit. Ballistët kanë qenë besnikë ndaj aleancës; por, pas kapitullimit italian, Enver Hoxha i kishte sulmuar ata, sepse ai nuk donte të ndante me rivalët çmimin e pushtetit politik. Lufta civile nuk ka lidhje me përpjekjet për Çlirimin Kombëtar, të cilën e kishin ndjekur të dyja palët në fillim. Partizanët, sidoqoftë, e kanë treguar veten të pamëshireshëm për çmimin e luftës që paguante popullsia civile dhe të fortë me armët që morën nga britanikët. Ata kanë trysnuar fort ndaj ballistëve; dhe, këta të fundit, duke e pasur të pamundur një luftë në dy frontet, kishin qenë të detyruar t’i pezullojnë sulmet e tyre ndaj gjermanëve, që të mund të mbrojnë veten ndaj partizanëve. (When the meal was over, we turned to grimmer topics. We bluntly accused the Balli Kombetar of “collaborating” with the Germans and threatened to denounce the movement and its leaders as enemies of the Allies unless they at once abandoned their fight against the Partisans. Midhat Bey was too honest to dissemble and answered that it was now too late. A revolution was in progress in South Albania in which the Communists, organised in the L.N.Ç., sought to overthrow the existing social order defended by the Balli Kombetar. Both movements had their origin in the resistance to the Italians, and at Mukai, in 943, had concluded an alliance for joint operations against the Axis armies. The Ballists had been loyal to the alliance; but, after the Italian capitulation, Enver Hoja had attacked them, so that he should not have to share with rivals the prize of political power. This civil war had no connection with the struggle for National Liberation, which both parties had at first continued to prosecute. The Partisans, however, had shown themselves reckless of the cost of war to the civilian population and strong in the arms they received from the British. They had pressed hard upon the Ballists; and the latter, unable to sustain a war on two fronts, had been forced to suspend their attacks on the Germans that they might defend themselves against the Partisans.)

Mid’hat Frashëri: Nëse Enver Hoxha heq dorë nga revolucioni socialist, Ballistët me kënaqësi do të luftojnë prapë kundër gjermanëve

Ishte për të ardhur keq që lufta civile kishte marrë përparësi ndaj zhvillimeve të tjera, por ky ishte realiteti tashmë, iu thotë Mid’hat Frashëri bashkëbiseduesve të tij britanikë. “Gjermanët tashmë ishin mundur dhe shqiptarët mund të bëjnë pak për të shpejtuar apo vonuar shkatërrimin e tyre. Pasoja e luftës civile, sidoqoftë, ishte ende në dyshim dhe kishte prekur çdo aspekt të jetës së përditshme të çdo shqiptari. Ai nuk mund t’i fajësonte vërtet ata udhëheqës Ballistë të cilët, për aksione të veçanta, kishin pranuar ndihmën nga ushtria gjermane. Ata e nuk e kishin bërë këtë nga dashuria për gjermanët as nga përllogaritjet se Gjermania prapë mund të fitojë, por thjesht sepse njerëzit përpiqen të marrin çdo masë për të zgjatur, madje edhe nëse ata nuk mund të shpresojnë t’ia arrijnë, për të ruajtur jetën dhe pasurinë. Partizanët ende po luftojnë kundër gjermanëve, por ata po e bëjnë këtë në një shkallë të vogël dhe vetëm për të marrë armë dhe furnizime nga Aleatët me të cilat ata ta vazhdojnë revolucionin e tyre. Nga çdo njëqind armë që ne ua dërgojmë atyre, nëntëdhjetë zbrazen kundër shqiptarëve. Ai na u lut ne, prandaj, që t’i përmbajnë partizanët, duke shtuar se nëse Enver Hoxha do ta braktiste përpjekjen për ta kryer revolucionin social nën petkun e rezistencës patriotike, atëherë Ballistët me kënaqësi do të luftojnë prapë kundër gjermanëve. Ballistët, argumentoi ai, ishin miqtë e britanikëve; partizanët ishin vetëm agjentë të Rusisë. Ai na kërkoi ne, prandaj, që të mos e përdorim ndikimin tonë ne Shqipëri për të vrasjes së më shumë ushtarëve të një ushtrie që tashmë është mundur. ” (The out come of the civil war, however, was still in doubt, and affected every aspect of the daily life of each Albanian. Nor could he really blame those Ballist leaders who, for particular actions, had accepted help from the German army. They had done so neither out of love for the Germans nor from any calculation that Germany might still win, but simply because men will adopt almost any expedient whereby they may prolong, even if they cannot hope to preserve, the enjoyment of life and property. The Partisans might still be fighting the Germans, but they did so on a small scale and solely so as to obtain arms and subsidies from the Allies with which to prosecute their revolution. Out of every hundred rounds which we sent them ninety would be fired against Albanians. He begged us, therefore, to restrain the Partisans, adding that if Enver Hoja would abandon the attempt to carry out a social revolution under the guise of patriotic resistance, then the Ballists would gladly join once more in the struggle against the Germans. The Ballists, he argued, were our friends; the Partisans were only agents of Russia. He urged us, therefore, to consult our imperial interests and not to sign away our influence in Albania for the sake of killing a few more soldiers of an army that was already beaten.)

Amery: Ne i hodhëm poshtë argumentet e Mid’hat Frashërit, por me veten tonë pranuam se kishte shumë të vërtetë në atë që tha ai

“Ne i hodhëm poshtë me forcë argumentet e tij duke mos lënë asnjë shenjë simpatie nga ne që mund të trimëronte formimin e një fronti antikomunist. Megjithatë, ne do ta pranonim me veten tonë se kishte shumë të vërtetë në atë që tha ai. Kjo është nga një largësi: duke parë rrjedhën e revolucioneve vëren se shumë shpesh te ato nuk mund të ketë asnjanësi. Kur një betejë është në vazhdim në një fshat apo rajon të veçantë, asnjë burrë i aftë fizikisht, pa përmendur këtu çdo njeri me influencë, i cili është fizikisht i pranishëm, nuk mund të shmang paanësinë. Ata që do të kërkojnë të mbeten pasivë pashmangshëm ngjallin dyshimin ose lakminë e luftëtarëve, dhe është vetëm çështje fati nëse ata qëllohen si spiunë, vriten për pasurinë e tyre apo i kap ndonjë plumb qorr. Në kohën e revolucionit “Ai që nuk është me mua, është kundër meje.”” (We sternly rejected his arguments lest any sign of’ sympathy from us should encourage the formation of an anti-Communist front. Nevertheless, we had to admit to ourselves that there was much truth in what he said. Those is from a distance; observe the course of revolutions too often fore et that in them there can be no neutrality. When a battle is in progress in a particular village or district no able-bodied man, let alone any man of influence, who is physically present, in avoid taking sides. Those who would seek to remain passive inevitably arouse the suspicion or the greed of the combatants, and it is only a question of chance whether they are shot as spies, muredered for their property, or killed by a stray bullet. In time of revolution, “He that is not with me is against me”.)

Amery: Britanikët kundërshtuan çdo përpjekje për një front antikomunist në Shqipëri

Kështu thekson Amery, në bisedën me Nuredin Bej Vlorën, bir i vezirit të madh Ferid Pasha dhe nip i Ismail Qemalit, themluesit të parë të republikës shqiptare, të cilin britaniku e përshkruan si pronar të madh tokash, i dënuar me vdekjes pastaj i falur nga Zogu si pjesëtar i Revolucionit të Fierit dhe si një nga përkrahësit më me ndikim të Partisë Republikane. Amery, pra, e konsideron Ballin Kombëtar si vijim të Partisë Republikane Shqiptare. “Ne u kënaqëm me rehatinë në shtëpinë e Ihsanit dhe iu shpjeguam kundërshtimin tonë të patundur ndaj çdo fronti antikomunist politikanëve të ndryshëm që erdhën nga Tirana për të na takuar ne,” shkruan Amery. (Next day we enjoyed the comforts of Ihsan’s house and expounded our inflexible opposition to an anti-Communist front to various lesser politicians who came out from Tirana to meet us.)

Pra, politika e britanikëve, kështu edhe e aleatëve perëndimorë ishte e patundur në vendosmërinë për të kundërshtuar çdo front antikomunist në Shqipëri. Ky është një realitet katërcipërisht i kundërt me realitetin që jep Enver Hoxha në librin e tij “Rreziku Anglo-Amerikan në Shqipëri”.

Amery, një bashkëbisedues dhe dëshmitar me kujtesë të fortë dhe aftësi të rralla përshkruese e interpretuese

Julian Amery vinte në karrierën ushtarake me përvojën e tij si korrespondent shtypi në Luftën Civile të Spanjës dhe si oficer i shërbimit britanik MI6. Ai, veç të tjerash, është i pajisur me një kujtesë të fortë, me një aftësi të rrallë për të regjistruar gjithçka sheh dhe dëgjon, çdo fytyrë, çdo tipar, çdo psikologji, çdo shprehje fytyre. Edhe në këto kujtime ai e ruan stilin e raportuesit nga fronti. Librin e tij, ku përshihen edhe këto kujtime për Mid’hat Frashërin ai e boton për herë të parë në vitin 1948, katër vjet pas zhvillimit të ngjarjeve, kur çdo hollësi është ende e freskët në kujtesën e tij. Autor i mëvonshëm i shumë librave, Amery është një penë e stërvitur qysh në këtë libër kujtimesh.

Mid’hat Frashëri sot fizikisht përsëri i pranishëm

Kthimi i eshtrave – sipas amanetit të tij – në Shqipëri dhe vendosja pranë babait e dy xhaxhallarëve, e ka bërë të pranishëm fizikisht Mid’hat Frashërin 74 vjet pas arratisjes dhe 69 vjet pas vdekjes. Në këto vite ai ishte një i dënuar me vdekje, një i ndaluar të kthehet në Shqipëri gjallë apo vdekur, ishte i dënuar kështu me mungesë shpirtërore dhe fizike. Dënimi më i madh kundër Mid’hat Frashërit ishte mungesa e lejimit të fjalës. Asgjë që ka shkruar me emrin e tij apo pseudonimin e tij Lumo Skëndo nuk është lejuar të përmendet në Shqipëri, asgjë që ka thënë ai, nuk është lejuar të rikujtohet në Shqipëri, përveç një strofe në “Epopenë e Ballit Kombëtar”.

Pas vitit 1990 Mid’hat Frashëri nuk është më një mungesë shpirtërore. Atij i lejohej fjala nëpërmjet veprës së tij, nëpërmjet kujtimeve të bashkëkohësve të tij, nëpërmjet historisë në rishkrim e sipër. Tashmë është edhe një prani fizike. Mohuesit e tij, tashmë deri në brezin e tyre të tretë e të katërt, ndihen të çarmatosur.

Ata e krahasojnë me Naimin, Abdylin, Samiun me qëllim që ta zvogëlojnë. Me të njëjtin qëllim e krahasojnë me bashkëkohës si Noli dhe Konica. Për t’ia vënë në dyshim përmasat e atdhetarit, përmasat e politikanit, përmasat e intelektualit. Duan ta fajësojnë pse në periudha të ndryshme më shumë te ai është shquar atdhetari, pse në periudha të tjera më shumë te ai është shquar intelektuali, pse në periudha të tjera më shumë është shquar polititikani.

Mid’hat Frashërit tashmë nuk i mbyllet dot goja. Dhe pasi e ka edhe historinë me vete, Mid’hat Frashërit as që i mbahet më goja. Ai flet rrjedhshëm dhe pandalshëm për të vërtetën.

***

Siç premtova në fjalinë e parë të këtyre shënimeve, Mid’hat Frashërin e solla nëpërmjet kujtimeve të britanikut Julian Amery, nëpërmjet vlerësimeve dhe citimeve që ia bën ky bashkëbisedues i shquar dhe ky dëshmitar i lartë i Mid’hat Frashërit e i periudhës së kur në Shqipëri ishte në “përparim Revolucioni Komunist” i Enver Hoxhës kundër Ballit Kombëtar, kundër nacionalistëve, kundër çdo kundërshtari të mundshëm të Enver Hoxhës në luftën për pushtet. Tekstet e britanikut Julian Amery, respektivisht faqet 183, 184, 185 të librit të tij “Sons of Eagle: A Study in Guerila War” (Bijtë e shqipes: një studim për luftën guerile), publikuar nga shtëpia botuese Macmillan, (botim i parë, 1948) ne i kemi botuar dy herë të plota në faqet e botimit tonë voal.ch.

Midhat Frashëri – Julian Ameryt: Ja pse u detyruam t’i pezullojmë sulmet kundër gjermanëve

***

Julian Amery, Sons of Eagle: A Study in Guerila War, published by Macmillan, first edition 1948

……set in green and shady gardens. There lay the prize for the victors in this many-sided struggle.

Ihsan’s house was situated in the plain to the north-west of Tirana and some five hours’ march from the mountain village of Priske, where we stopped for our evening meal. The presence of German patrols made it dangerous to go do\n into the plain before dark and required us to reach our destination before dawn. Ihsan had sent an escort of his bodyguards to meet us, but we sat too long over our meal and scarcely led ourselves true for the journey. The darkness of the night concealed us from the enemy, but it equally obscured from us the many pitfalls by which our path was beset. The tracks leading down from the mountain were slippery, for it had been raining; and I fell over several times. Once in the plain the way led along a dry watercourse, filled with ankle-spraining stones and short, thorny scrub. (Down at sea-7 v el the, night was hot and dank; and clouds of mosquitoes tormented our brief halts. But brief they were; for the guides kept an anxious watch on the eastern mountains, where the sky would first grow pale, and loped ahead, coaxing us on with false assurances that we should soon be there. At last the rumble of lorries warned us that we were approaching a road. This was the dust track along which traffic between Tirana and the North had been diverted since the destruction of the Gyoles bridge. We crossed the track between two convoys — a pleasing tribute to Smiley’s work — and, passing through a. stretch of woodland, merged into a broad meadow just as day was breaking.

In the meadow stood Ihsan’s house, one-storied and whitewashed, like many of the smaller country houses in Hungary. A light was burning in one of the windows; and, as we crossed the lawn, Ihsan Bey came out to welcome us. He led the way indoors through mosquito curtains, for the plains are malarial; and we found ourselves for the first time in two months in a civilised room. There were armchairs and sofas; books and magazines lay on the table; pictures hung on the walls; and in a corner stood a luxurious radiogram. We stacked our submachine-guns and accoutrement of war beside it and sat down, feeling distinctly out of place amid these comfortable surroundings, with our unkempt hair, dirty uniforms, and heavy boots.

Ihsan Bey was still in his early thirties, a well-built and `rather studious-looking man, dressed in a grey flannel suit with a: white shirt open at the neck. He had studied in Vienna, and indeed might well have been an Austrian country gentleman from his small talk, the cut of his clothes, and the slightly German turn of his English sentences. An attentive host, he plied us in quick succession with tea, coffee, and a very potent raki, while we explained the purpose of our visit. Then, seeing that we were tired, he led us to our bedrooms, where clean pyjamas had been laid out. For the first time in months we slept between linen sheets and forgot the fatigues of the march in the delights of a spring mattress. It was after midday when we awoke to the comforts of modern lavatories and hot, scented baths; superfluous luxuries for a guerilla, but doubly welcome for their strangeness.

In the morning, while we still slept, Ihsan had driven into Tirana on our business. He returned about two o’clock, accompanied by Nureddin Bey Vlora, the friend of Count Carlo Frasso, our host at Brindisi, and by a younger man with a charming, French-speaking wife. Nureddin Bey was a son of the Ottoman Grand Vizier, Ferid Pasha, and a nephew of Ismail Kemal, the founder of the first Albanian Republic. A great landowner in the region of Valona, he had been condemned to death, though later pardoned, for his part in the Fieri revolution against King Zog and had long been one of the most influential supporters of the Republican Party. He was too great a patriot and too proud to “collaborate” with either the Italians or the Germans, but his counsels weighed heavily with the political leaders in Tirana, and especially with the Republican chiefs of the Balli Kombetar.

Still in his forties, Nureddin was fit-looking, debonair, and very much a man of the world. He was dressed in a smart white suit and might just have stepped out of the casino at Mentone or the Mohammed Ali Club in Cairo. His English was faultless, and with a sure understanding of the British character he brought us whisky, for which he had combed Tirana, and excellent cigarettes made of Albanian tobaccos specially blended to his taste. At lunch the talk skimmed lightly from anecdotes to mutual acquaintances in the capitals of Europe; and, with the added charms of feminine company, the barriers of nationality and politics were seemingly dissolved by the pleasures of social intercourse. Such a gathering of Albanian landowners and British officers must have appeared to a Partisan observer as proof positive of the sinister machinations of international reaction. The thought passed through my mind, but I cannot pretend that it seriously diminished my enjoyment of the occasion.

When we had eaten, Ihsan took the other guests apart, and we remained alone with Nureddin. He told us at once that he had just been invited by the Germans either to assume the Premiership or to enter the Council of Regency. His natural instinct had been to decline the thankless task, but he would accept the responsibility if he could thereby assist the Allied cause. The idea of having a friend as head of the “collaborationist” government was certainly tempting and might offer opportunities for attacking the Germans from within. Nevertheless, we strongly advised Nureddin to refuse an invitation which might lead other Albanian Nationalists to line up with the Germans in an anti-Communist front. We then expounded our general policy’, condemning collaboration in any form and stressing that we could only support those Albanians who fought against the Germans. We spoke, too, of our concern that the Ballists should be fighting with the enemy against the Partisans and appealed to Nureddin to use his influence with their leaders to bring about a change of policy. He told us that the Ballists would not only cease fighting the Partisans but would gladly co-operate with them against the Germans if only Enver Hoja would abandon his attempt to impose a social revolution on Albania by force. If we could restrain the L.N.Ç. Iie was confident that the Ballists would prove amenable; if we could not, then they must fight as best they could, for their lives and property were at stake.

Ihsan drove Nureddin back to Tirana in the afternoon, and returned for dinner, bringing with him Midhat Bey Frasheri, the President of the Balli Kombetar. Midhat Bey had been in turn an official of the Sublime Porte, a member of the Committee of Union and Progress, and a powerful. influence in the early struggles of the Albanian state. He had retired from public life under the monarchy, for he was a strong Republican, and since then had eked out his living from the proceeds of a bookshop. Steeped in the cultures of Europe and of the Near East, he was a man of austere ways, a romantic conservative, possessed of burning patriotism and a Catonian faith in the virtues of aristocracy. Now over seventy years old, he was a spare, straight figure, with determined yet sensitive features and a skin like parchment. On first acquaintance he seemed inordinately shy and was afflicted with a slight stutter. He vas gifted, however, with a dry but sparkling wit, and his talk at dinner that night assured our entertainment and compelled our admiration.

When the meal was over, we turned to grimmer topics. We bluntly accused the Balli Kombetar of “collaborating” with the Germans and threatened to denounce the movement and its leaders as enemies of the Allies unless they at once abandoned their fight against the Partisans. Midhat Bey was too honest to dissemble and answered that it was now too late. A revolution was in progress in South Albania in which the Communists, organised in the L.N.Ç., sought to overthrow the existing social order defended by the Balli Kombetar. Both movements had their origin in the resistance to the Italians, and at Mukai, in 943, had concluded an alliance for joint operations against the Axis armies. The Ballists had been loyal to the alliance; but, after the Italian capitulation, Enver Hoja had attacked them, so that he should not have to share with rivals the prize of political power. This civil war had no connection with the struggle for National Liberation, which both parties had at first continued to prosecute. The Partisans, however, had shown themselves reckless of the cost of war to the civilian population and strong in the arms they received from the British. They had pressed hard upon the Ballists; and the latter, unable to sustain a war on two fronts, had been forced to suspend their attacks on the Germans that they might defend themselves against the Partisans.

It was regrettable that the civil war should have taken precedence oven- the is of .1 iteration, but it w4 as not unnatural. The Germans were already beaten, and the Albanians could do little to hasten or retard their destruction. `I he out come of the civil war, however, was still in doubt, and affected every aspect of the daily life of each Albanian. Nor could he really blame those Ballist leaders who, for particular actions, had accepted help from the German army. They had done so neither out of love for the Germans nor from any calculation that Germany might still win, but simply because men will adopt almost any expedient whereby they may prolong, even if they cannot hope to preserve, the enjoyment of life and property. The Partisans might still be fighting the Germans, but they did so on a small scale and solely so as to obtain arms and subsidies from the Allies with which to prosecute their revolution. Out of every hundred rounds which we sent them ninety would be fired against Albanians. He begged us, therefore, to restrain the Partisans, adding that if Enver Hoja would abandon the attempt to carry out a social revolution under the guise of patriotic resistance, then the Ballists would gladly join once more in the struggle against the Germans. The Ballists, he argued, were our friends; the Partisans were only agents of Russia. He urged us, therefore, to consult our imperial interests and not to sign away our influence in Albania for the sake of killing a few more soldiers of an army that was already beaten.

We sternly rejected his arguments lest any sign of’ sympathy from us should encourage the formation of an anti-Communist front. Nevertheless, we had to admit to ourselves that there was much truth in what he said. Those is from a distance; observe the course of revolutions too often fore et that in them there can be no neutrality. When a battle is in progress in a particular village or district no able-bodied man, let alone any man of influence, who is physically present, in avoid taking sides. Those who would seek to remain passive inevitably arouse the suspicion or the greed of the combatants, and it is only a question of chance whether they are shot as spies, muredered for their property, or killed by a stray bullet. In. time of revolution, “He that is not with me is against me”.

Next day we enjoyed the comforts of Ihsan’s house and expounded our inflexible opposition to an anti-Communist front to various lesser politicians who came out from Tirana Jo meet us. The rest of the time we spent in discussions with Ilhsan and his cousin., Liqa, who was renowned as a hunter. Ihsan disapproved of blood sports but, since the chasse a l’homme was a frequent feature of Albanian country life, he kept two machine-guns, a mortar, and a stock of hand-grenades in his gun-room as a matter of course. In the house he carried only a light automatic, but when he drove to Tirana, or went for a walk, he armed himself with a Mauser parabellum. Such precautions seemed incongruous in so civilised a man; but, if blood feuds were less common in the plain than in the mountains, the preventive assassination of opponents was a time-honoured method of government. It was interesting, indeed, to see how centuries of despotic rule had engrained the habits of conspiracy in the life of an Albanian country gentleman. One evening at dinner I heard what I thought was an owl hooting in the garden.

“It must be my cousin Liqa”, said Ihsan, going to the French windows, “it is his call.”

Sure enough it was.

We left Ihsan by night and set out towards our base, stopping in the mountains above Tirana to meet Jem al [tern, Jemal had once been chief of Zog’s secret police, and, along with Muharrem. Bairaktar, Prenk Previsi, and Fikri Dine, had formed the quadrumvirate by whose efforts the royal regime had been established. Like his colleagues, he had fallen from favour, but had followed Zog into exile in 1939, returning to Albania in 1941 with Oakley-Hill and the forces of the Unites! Front. Now he stood second to Abas Kupi in the Zogist movement and had built up a small but efficient force of his own….